Recently my scientific curiosity was piqued after watching this edited short piece from the TED talk by Susan Pinker. Her presentation titled “The secret to living longer may be your social life” explored (as described in the video) the “least to strongest predictors of reducing your chances of dying”. Now let me be clear. It not my intention to dispute the central argument of Pinker’s presentation, which is that strong social relationships, good social integration and minimal social isolation are all critically important to our wellbeing, as the data shows that this is so. What I do want to contest, however, is her claims made regarding the effects of exercise on mortality, as this is what primarily interests me as an Exercise Scientist. I wanted to confirm that what was presented actually reflects the current body of evidence and the latest science published in this area. My contention is that what she presented in the abovementioned TED talk does not in fact do this. I have not researched whether the effect sizes purported for other parameters (such as smoking, alcohol, obesity etc) hold up. I did initially suspect that the effect size reported for exercise was outdated. After assessing the research and literature, there are a number of erroneous claims made and outdated science used that, in my opinion, require critique and comment.

Pinker cites the work of Julianne Holt-Lunstad and states the following (taken directly from the transcript):

6:22

Now, these centenarians’ stories along with the science that underpins them prompted me to ask myself some questions too, such as, when am I going to die and how can I put that day off? And as you will see, the answer is not what we expect. Julianne Holt-Lunstad is a researcher at Brigham Young University and she addressed this very question in a series of studies of tens of thousands of middle aged people much like this audience here. And she looked at every aspect of their lifestyle:their diet, their exercise, their marital status, how often they went to the doctor, whether they smoked or drank, etc. She recorded all of this and then she and her colleagues sat tight and waited for seven years to see who would still be breathing. And of the people left standing, what reduced their chances of dying the most? That was her question.

07:19

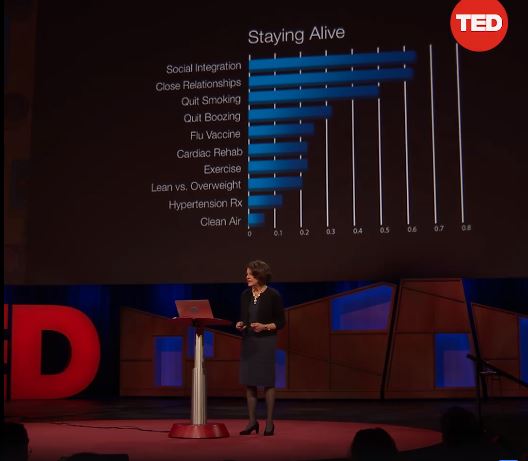

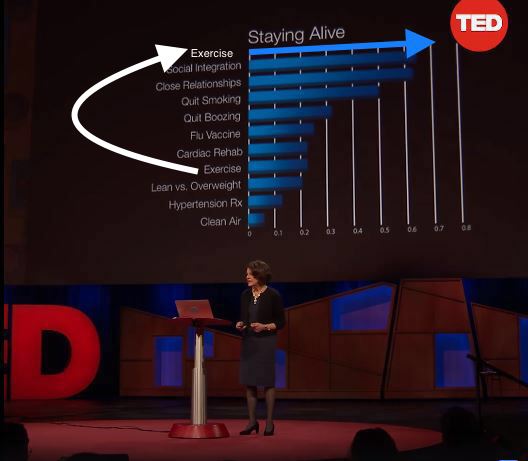

So let’s now look at her data in summary, going from the least powerful predictor to the strongest.OK? So clean air, which is great, it doesn’t predict how long you will live. Whether you have your hypertension treated is good. Still not a strong predictor. Whether you’re lean or overweight, you can stop feeling guilty about this, because it’s only in third place. How much exercise you get is next, still only a moderate predictor. Whether you’ve had a cardiac event and you’re in rehab and exercising,getting higher now. Whether you’ve had a flu vaccine. Did anybody here know that having a flu vaccine protects you more than doing exercise? Whether you were drinking and quit, or whether you’re a moderate drinker, whether you don’t smoke, or if you did, whether you quit, and getting towards the top predictors are two features of your social life. First, your close relationships. These are the people that you can call on for a loan if you need money suddenly, who will call the doctor if you’re not feeling well or who will take you to the hospital, or who will sit with you if you’re having an existential crisis, if you’re in despair. Those people, that little clutch of people are a strong predictor, if you have them, of how long you’ll live. And then something that surprised me, something that’s called social integration. This means how much you interact with people as you move through your day.How many people do you talk to? And these mean both your weak and your strong bonds, so not just the people you’re really close to, who mean a lot to you, but, like, do you talk to the guy who every day makes you your coffee? Do you talk to the postman? Do you talk to the woman who walks by your house every day with her dog? Do you play bridge or poker, have a book club? Those interactions are one of the strongest predictors of how long you’ll live.

Comments:

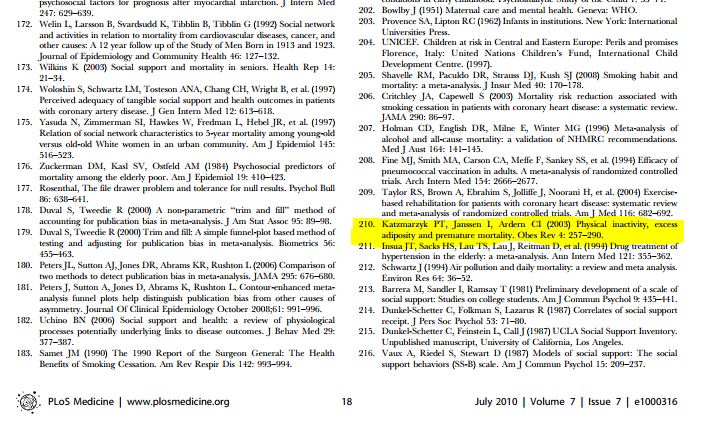

The 2 studies cited in the footnotes (notes and references) section in support of Pinker’s claims regarding the above are the following: a) “Social relationships and mortality risk: A meta-analytic review,” Holt-Lunstad, Julianne, Smith, Timothy R., and Layton, Bradley J, PLOS Medicine, 2010 and b) “Loneliness and Social Isolation as Risk Factors for Mortality,” Julianne Holt-Lunstad, Perspectives on Psychological Science, 2015. Both these studies were meta-analytical reviews conducted to determine the extent to which social relationships and social isolation influence risk for mortality. They clearly and rightly show that the quality and strength of the social relationships, social integration and social isolation that we experience are key determinants and predictors of premature death.

However, Holt-Lunstad’s research and her meta-analytical studies did not directly collect, analyse or assess the impact of diet, exercise, obesity, alcohol, smoking etc over a 7-year period on mortality as claimed by Pinker. This data was extracted from other meta-analyses that were performed by other researchers.

Let’s look at the graph that Pinker uses to illustrate her argument.

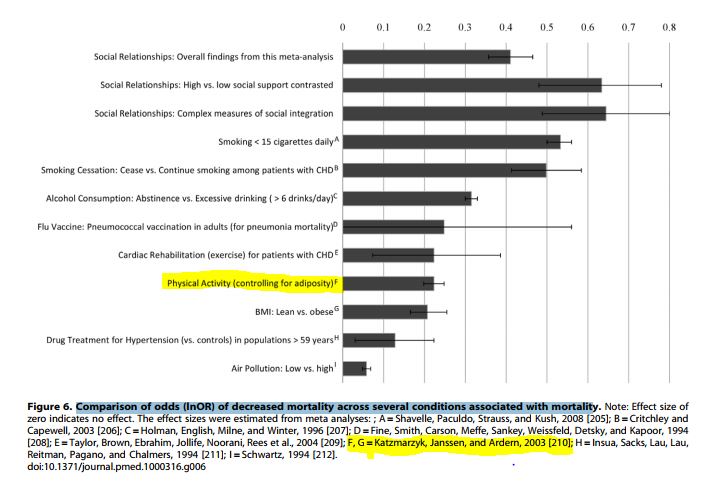

The graph used by Pinker in her presentation is a modification of this graph (see below and click on for a clearer image) from the paper “Social relationships and mortality risk: A meta-analytic review,” Holt-Lunstad, Julianne, Smith, Timothy R., and Layton, Bradley J, PLOS Medicine, 2010

As you can see the effect sizes for things like smoking, alcohol, exercise, obesity have not been derived from Julianne Holt-Lunstad’s primary research. These have been extracted from other meta-analyses that Holt-Lunstad had nothing to do with. You can see the letters against each predictor (eg smoking) and the associated reference with the effect size taken from this. Figure 6 was created to compare and contrast how important social relationships and connections are to us, with other well known influencers and determinants of mortality.

As an Exercise Scientist I was particularly curious by Holt-Lunstad’s ranking of exercise in the least to strongest predictors graph as depicted in her paper and was very keen to have a look at this research given that the claims promulgated by Pinker hinges on this evidence.

As you can see in the picture above (highlighted in yellow) the effect size used for exercise was taken from this study: Katzmarzyk, Janssen, and Ardern, 2003 [210]. A 15-year-old meta-analysis. Here’s a screenshot of the reference list with the highlighted study used to rank exercise in Pinkers graph above.

The key questions in my mind are:

- Does the Katzmarzyk et al. (2003) meta-analysis still represent and reflect the best and most robust evidence currently available?

- Has there been any additional research since 2003 that has changed our understanding regarding the impact of exercise on all-cause, CVD-related and cancer-related mortality?

- Is the graph that Pinker hinges her “least and strongest predictors of how long you’ll live” argument on, still hold up?

The simple answers to these questions I believe, are no, yes and no.

One of the big changes in exercise research over the last decade or so is the development of, and refinement in how accurately physical activity and exercise can be measured. In earlier studies that assessed the effects of exercise on mortality, the methods utilised to ascertain the data on the amount of exercise performed was quite crude and was established subjectively. In other words, those involved in such studies were usually asked via a questionnaire how much exercise and/or physical activity do they do everyday/in a week? As you would appreciate data collected in this fashion is unlikely to be very accurate. It would not therefore be a true reflection of what participants were actually doing.

This is precisely the problem with the Katzmarzyk et al. (2003) meta-analysis that was used by Holt-Lunstad in her paper and which Pinker cites in her presentation, in that results were based on subjective determinations of exercise. More recent research has moved to much more accurate and nuanced methods to establish the magnitude and intensity of physical activity and exercise in such studies.

Devices known as accelerometers have revolutionised the objective daily measurement of exercise and physical activity. Over the last few years several studies have been published that have used accelerometers to determine objective levels of exercise/physical activity. Some of the first to use triaxial devices (capable of measuring activity along 3 planes), which increase the sensitivity for recognising physical activity, are now appearing in scientific journals and thus give us a much more insightful picture into the role or impact of exercise and physical activity on mortality (see here).

Now you may be curious or wondering, what do these studies tell us about this relationship and is it any different to the Katzmarzyk et al. (2003) meta-analysis used by Holt-Lunstad in her above graph and cited by Pinker in her TED presentation?

Let’s take a look at some of the key findings from some of these accelerometer-based studies. In brief, Lee et al. (2017) found that there was a strong inverse association between overall volume of physical activity and all-cause mortality. In fact, the magnitude of risk reduction (≈60%–70%; comparing least to most active) was far larger than that estimated from meta-analyses of studies using self-reported PA (≈20%–30%). In the Dohrn et al. (2017) study, compared with the least sedentary participants (i.e. those with the highest levels of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity or MVPA), those in the most sedentary group had an increased risk of all-cause mortality, hazard ratio: 2.7, CVD mortality, hazard ratio: 5.5 and cancer mortality, hazard ratio: 4.3. These hazard ratios are substantial. Those that spent the most time in MVPA showed huge risk reductions for all-cause mortality (over 60%), CVD mortality (almost 90%) and cancer mortality (over 80%). Evenson et al. (2016) found that having higher accelerometer-assessed average counts per minute was associated with lower all-cause mortality risk. The adjusted hazard ratio was 0.37 for those most active when compared to those most inactive; a 63% risk reduction in mortality. Results were similar for CVD mortality.

What does this mean for the graph that Pinker used in her presentation that I have been discussing. In short, a lot. The influence and impact of exercise and physical activity on mortality is far stronger than many acknowledge or give credit. Based on more recent research that is able to accurately quantify levels of physical activity and exercise, particularly MVPA, much greater promotion, awareness and utilisation (and rightly so) should be placed on one of the most powerful ways of reducing your chances of premature death. Unfortunately, this TED talk by Susan Pinker cites what is arguably outdated 15-year old exercise data that diminishes and misconstrues – to a significantly large and impressionable audience – the very strong inverse relationship that exists between physical activity and mortality. This needs to be called out, so here you go, I am calling this out as loudly as I can.

NB. Whilst the above blog focused on the veracity of data used, and claims made for exercise in the discussed presentation, it remains to be seen as to whether the other predictors in the graph (excluding the social relationships data) are accurate and robust. I would therefore suggest that one should be mindful of this when watching this TED talk.

For local Townsville residents interested in FitGreyStrong’s Exercise Physiology services or exercise programs designed to improve physical fitness, health and quality of life or programs to enhance athletic performance, contact FitGreyStrong@outlook.com or phone 0499 846 955 for a confidential discussion.

For other Australian residents or oversees readers interested in our services, please see here.

Disclaimer: All contents of the FitGreyStrong website/blog are provided for information and education purposes only. Those interested in making changes to their exercise, lifestyle, dietary, supplement or medication regimens should consult a relevantly qualified and competent health care professional. Those who decide to apply or implement any of the information, advice, and/or recommendations on this website do so knowingly and at their own risk. The owner and any contributors to this site accept no responsibility or liability whatsoever for any harm caused, real or imagined, from the use or distribution of information found at FitGreyStrong. Please leave this site immediately if you, the reader, find any of these conditions not acceptable.

© FitGreyStrong

Brilliant work. Nice job driving accountability and making your thought process and research concise and easy to read. Well done! -Ryan

Kudos for taking the time to source and digest the evidence for us, Sean. I’ve been wearing my nerd glasses and spotted a smattering of technical misdemeanors in crafting their hypothesis and conducting their meta-analysis. In this respect,

Keep up the good work

Thanks Fergal. Was actually quite surprised once I started looking more closely at what was presented. Knowing the challenges that confront us in terms of increasing people’s engagement and participation in exercise and physical activity, I was not overly impressed, particularly when based on outdated evidence. I suspect, however, that this was an inadvertent mistake, in that the presenter was just not aware that our understanding of, and insights into the relationship between exercise and mortality have substantially moved forward.