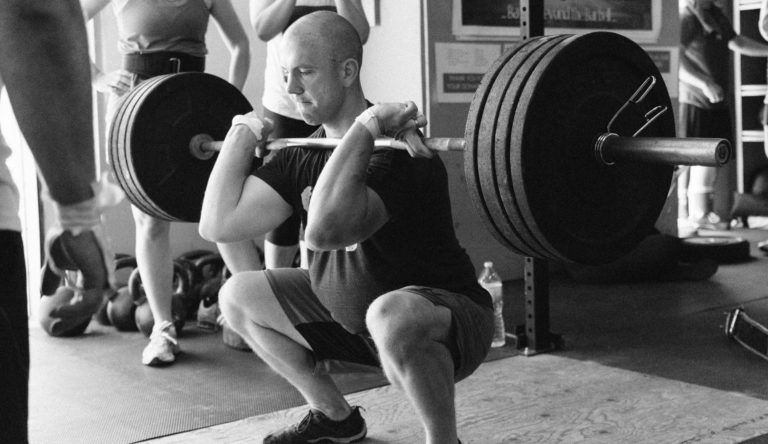

Two Exercises That Anyone Over 55+ Must Do!

This video is a must-watch for anyone over 55. In 13 minutes, FitGreyStrong explores 2 muscle groups – the Hip Flexors and the Dorsiflexors – that are often overlooked or simply just ignored, but which are crucial to maintain stability and high physical functioning in older adults. Crucially, the presentation helps explain what these muscle…