Resistance Training for Older Adults: 12 Evidence-Based Reasons (Part 1)

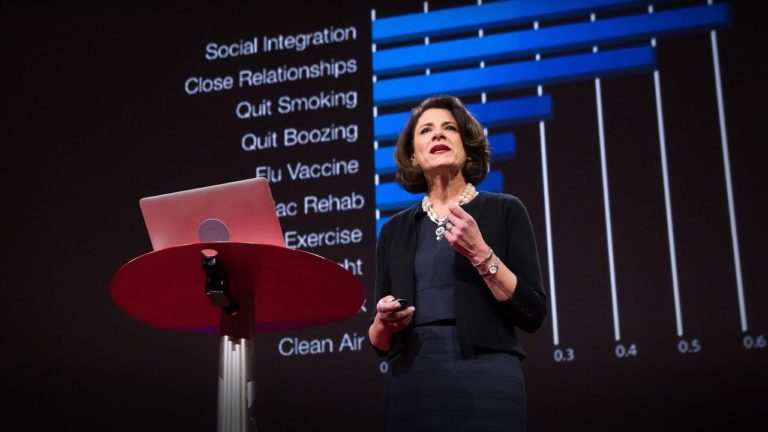

What are benefits of resistance training for older adults? Increases longevity and improves quality of life Helps manage hypertension and decreases heart disease Enhances sleep quality and quantity Prevents/treats type 2 diabetes & decreases inflammation Prevents cognitive decline & neurodegenerative disease Improves mental health Enhances skeletal health Maintains or increases lean body mass (muscle) Increases strength, power,…