I’d like to talk about something that’s become very personal to me: stroke. Recently, someone very close to me suffered a stroke, for which they are currently receiving very intensive treatment in the hope of making a recovery. The family, as you can imagine, has been terribly distressed by what has happened and we all hope for the best outcome. It’s a stark reminder of how fragile our health can be and how crucial it is to take proactive steps to protect it. This experience has driven me to write this article to increase our understanding of stroke, promote better awareness, and to encourage everyone to not take their health for granted.

What Is a Stroke?

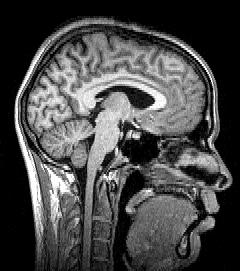

A stroke occurs when blood flow to the brain is interrupted, either due to a blockage (ischemic stroke) or a rupture of a blood vessel (hemorrhagic stroke). In Australia, approximately 50,000 people experience a stroke each year, with around 472,000 Australians living with the effects of stroke, making it one of the leading causes of death and disability in the country (Stroke Foundation, 2021). The consequences can range from mild impairments to severe disability, depending on the area of the brain affected.

How to Prevent a Stroke

Prevention is always better than cure, right? Here are some key steps to lower your risk:

- Maintain a Healthy Diet: A diet rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and lean proteins can reduce stroke risk by controlling blood pressure and cholesterol levels. The DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) diet has been shown to significantly lower blood pressure (Mozaffarian et al., 2011).

- Regular Exercise: Engaging in at least 150 minutes of moderate aerobic activity weekly can decrease stroke risk by approximately 30-40% (Aune et al., 2016). Exercise helps maintain a healthy weight and reduces blood pressure.

- Control Blood Pressure: High blood pressure is the leading risk factor for stroke. Studies suggest that lowering blood pressure by as little as 5 mmHg can reduce the risk of stroke by 34% (Wang et al., 2014).

- Quit Smoking: Smoking increases the risk of stroke by 2 to 4 times. Quitting can significantly lower this risk over time (Roth et al., 2018).

- Limit Alcohol Consumption: Moderate alcohol consumption is defined as up to one drink per day for women and two for men. Excessive drinking increases stroke risk, with studies showing that heavy drinkers have a higher incidence of hemorrhagic stroke (Bagnardi et al., 2001).

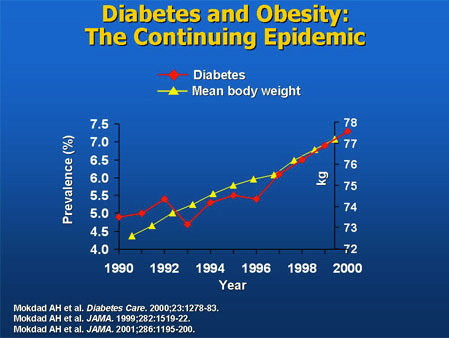

- Manage Chronic Conditions: Conditions like diabetes and high cholesterol can elevate stroke risk. Effective management of these conditions is crucial for prevention (Gorelick et al., 2011).

If a Stroke Happens: Recovery Is Possible

Now, let’s talk about what happens if a stroke occurs. Recovery can be challenging, but it’s absolutely achievable. This is where strength training comes into play, particularly the concept of neuroplasticity—the brain’s ability to reorganize itself by forming new neural connections (Kleim & Jones, 2008).

After a stroke, rehabilitation often focuses on restoring lost functions, and strength training can be a key component. When you engage in strength training for the unaffected limb, there can be surprising benefits for the affected side, often referred to as cross-education.

Unilateral Strength Training and Cross-Education

What does this mean? Let’s say a stroke affects your right arm. If you focus on strength training your left arm, research shows that you may actually gain strength in your right arm as well, even though it isn’t directly being trained. A meta-analysis found that unilateral strength training can result in a strength increase of up to as high as 29% in the contralateral limb (Green & Gabriel, 2018). This occurs because the brain activates mirror neural pathways that can enhance strength in the affected side by stimulating the unaffected side.

Enhancing Physical Function and Quality of Life

Strength training doesn’t just aid in muscle recovery; it also improves overall physical function. For stroke survivors, regaining strength can lead to better mobility, increased independence, and improved quality of life. A study published in the Journal of NeuroEngineering and Rehabilitation found that strength training improved not only muscle strength but also functional abilities in stroke survivors (Lohse et al., 2014).

Moreover, engaging in strength training can boost mental well-being. Exercise releases endorphins, natural mood enhancers. For those recovering from a stroke, this can be invaluable for combating frustration or depression that often accompanies recovery.

Evidence-Based Interventions for Recovery

While strength training is a crucial part of rehabilitation, it’s not the only strategy that can enhance recovery. A multi-faceted approach incorporating various interventions has shown promising results.

- Dietary Interventions: Nutrition plays a significant role in recovery. Diets rich in omega-3 fatty acids (found in fish, flaxseed, and walnuts) have been associated with improved outcomes post-stroke (Gao et al., 2019). Additionally, antioxidants found in fruits and vegetables help combat oxidative stress in the brain, potentially aiding recovery.

- Exercise Beyond Strength Training: In addition to strength training, aerobic exercise has been shown to improve cardiovascular fitness, functional independence, and overall well-being in stroke survivors (Billinger et al., 2014). Activities like walking, cycling, and swimming can enhance cardiovascular health and aid in weight management, further reducing stroke risk.

- Cognitive Rehabilitation: Cognitive impairments are common after a stroke, and engaging in activities that stimulate the brain can be beneficial. Playing games like chess, puzzles, or memory games can enhance cognitive function and may facilitate neuroplasticity (Tao et al., 2020). Studies show that cognitive training can lead to improvements in attention, memory, and executive functions.

- Mindfulness and Stress Reduction: Stress can negatively impact recovery. Techniques such as mindfulness meditation and yoga can promote relaxation and improve psychological well-being. Research suggests that mindfulness-based interventions can reduce anxiety and depression in stroke survivors, contributing to a more positive recovery experience (Chung et al., 2019).

- Supplementation: Certain supplements have shown promise in stroke recovery. For instance, B vitamins (particularly B6, B12, and folic acid) play a role in homocysteine metabolism, and elevated levels of homocysteine are linked to an increased risk of stroke. Supplementing with these vitamins may help improve outcomes, especially in individuals with deficiencies (Schnyder et al., 2019).

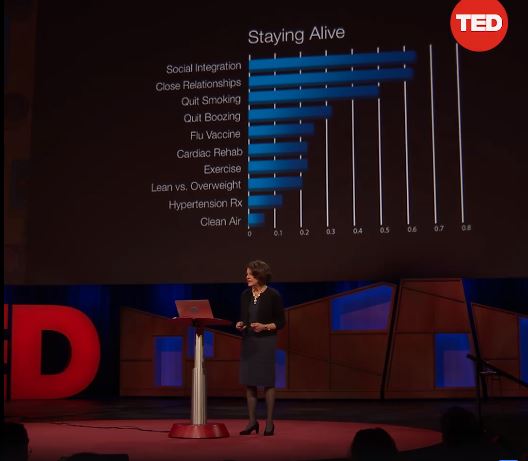

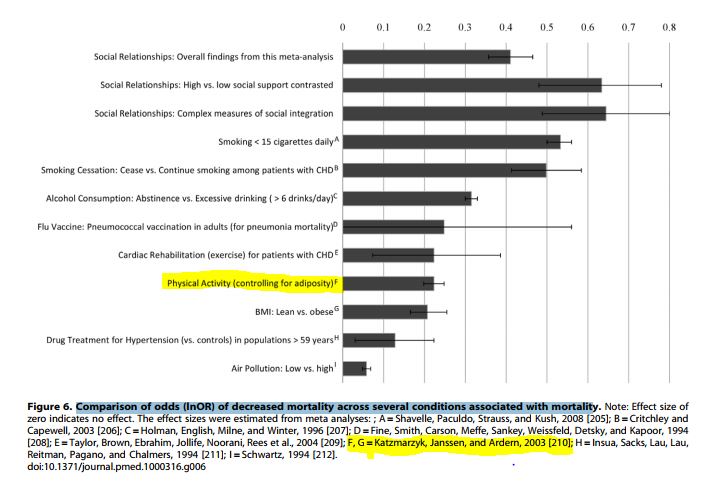

- Community Engagement: Social support is vital for recovery. Participating in community activities, support groups, or engaging with family and friends can enhance emotional well-being. A study found that strong social ties are associated with better recovery outcomes in stroke survivors (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2010).

- Exercise Physiology: Working with an Exercise Physiologist can help stroke survivors regain the physical capacity and skills needed for daily living. They can develop personalized plans that incorporate various interventions to improve strength, balance, fitness, motor skills, cognitive function, and independence.

- Speech Therapy: If language or communication skills are affected, speech therapy is crucial. Therapists can employ various strategies to help patients regain their speech abilities and improve their quality of life.

A Comprehensive Approach to Recovery

Taking a holistic approach to stroke recovery is essential. Combining strength training with dietary changes, cognitive activities, mindfulness practices, and therapy can maximize recovery outcomes. Each element plays a crucial role in rebuilding strength, coordination, cognitive function, and emotional well-being.

Before starting any exercise or dietary program post-stroke, consulting with a healthcare provider or rehabilitation specialist is crucial. They can help tailor a program that’s safe and effective for your specific situation.

The Road Ahead

Recovering from a stroke is undoubtedly a journey, but with the right strategies—like preventative measures, strength training, neuroplasticity, and a multi-faceted approach to recovery—you can make significant strides. Whether you’re looking to prevent a stroke or navigate recovery, understanding the power of your body and brain can be a game-changer.

Remember, you’re not alone on this journey. Whether you’re supporting a loved one or navigating recovery yourself, there are resources and support communities there to help. Let’s embrace the science of strength training, nutrition, cognitive engagement, and overall wellness as powerful tools for a healthier, stronger future!

So, how about making sure you allocate some time to move today? Take a walk, get on your bike, do some light strength training, or even dance around to your favourite music, it all counts.

Take care of your health!

Post-script: My father-in-law, Frank, passed away 17th October 2024. He was wonderful, loving and kind-hearted, the hardest of hard workers on his farm, and a man who was literally as strong as an ox. He will be sorely missed by many. RIP.

References

- Aune, D., et al. (2016). “Physical Activity and the Risk of Stroke: A Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies.” Stroke, 47(4), 1027-1035.

- Bagnardi, V., et al. (2001). “Alcohol Consumption and the Risk of Stroke: A Meta-Analysis.” Stroke, 32(11), 2558-2564.

- Billinger, S. A., et al. (2014). “Physical Activity and Exercise Recommendations for Stroke Survivors: A Statement for Healthcare Professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association.” Stroke, 45(8), 2535-2550.

- CDC. (2021). “Stroke Facts.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved from CDC.gov.

- Chung, M. L., et al. (2019). “Mindfulness-Based Interventions for Patients with Cardiovascular Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 34(5), 447-458.

- Gao, X., et al. (2019). “Omega-3 Fatty Acids and the Risk of Stroke: A Meta-Analysis.” Nutrients, 11(9), 2160.

- Gorelick, P. B., et al. (2011). “Diagnosis and Management of Stroke Risk Factors.” Stroke, 42(8), 2363-2369.

- Green, L. A., & Gabriel, D. A. (2018). The effect of unilateral training on contralateral limb strength in young, older, and patient populations: a meta-analysis of cross education. Physical Therapy Reviews, 23(4-5), 238-249.

- Holt-Lunstad, J., et al. (2010). “Social Relationships and Mortality Risk: A Meta-analytic Review.” PLoS Medicine, 7(7), e1000316.

- Kleim, J. A., & Jones, T. A. (2008). “Principles of Experience-Dependent Neural Plasticity: Implications for Rehabilitation After Brain Damage.” Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 51(1), S225-S239.

- Lohse, K., et al. (2014). “A Systematic Review of the Effect of Strength Training on Functional Recovery After Stroke.” Journal of NeuroEngineering and Rehabilitation, 11(1), 42.

- Mozaffarian, D., et al. (2011). “Global Cardiovascular Disease and Diabetes: Current Status and Future Directions.” Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 58(14), 1404-1410.

- Roth, G. A., et al. (2018). “Global and Regional Patterns in Cardiovascular Mortality from 1990 to 2013.” Global Heart, 13(3), 203-214.

- Schnyder, G., et al. (2019). “The Role of B Vitamins in Stroke: A Review.” European Journal of Neurology, 26(4), 569-577.

- Stroke Foundation. (2021). “Australia’s Stroke Statistics.” Retrieved from https://strokefoundation.org.au.

- Tao, J., et al. (2020). “Cognitive Training Improves Cognitive Function in Stroke Survivors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 101(5), 949-958.

- Wang, Y., et al. (2014). “Systolic Blood Pressure Reduction and Risk of Stroke: A Meta-Analysis.” Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 63(10), 1090-1098.