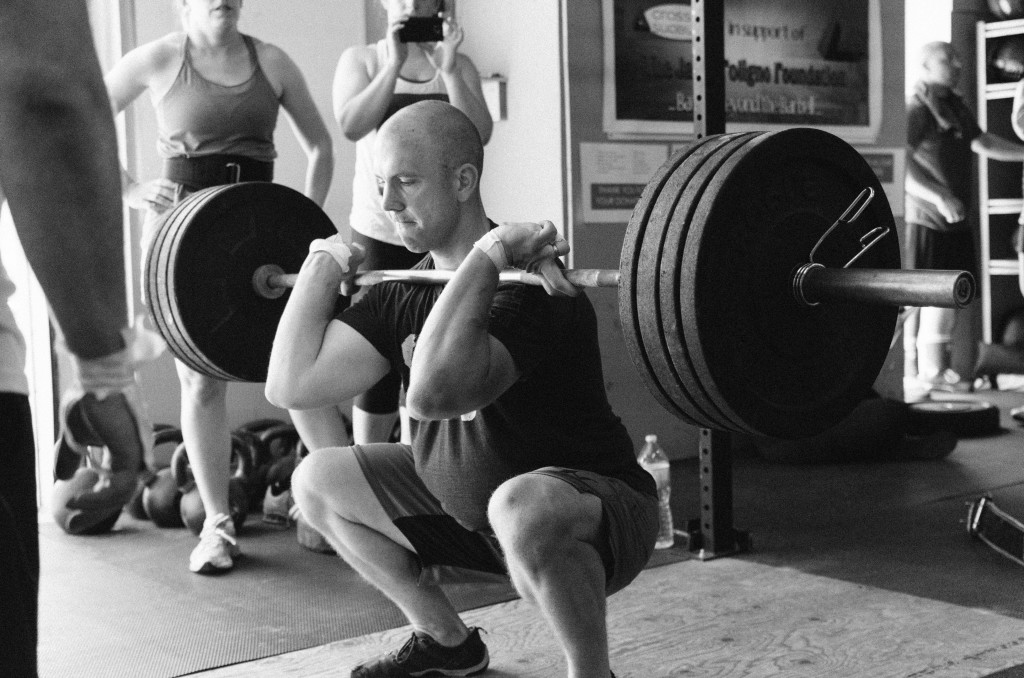

In part 1 of “12 reasons why older adults need to do resistance training exercise” I outlined some of the benefits to health that have been shown to occur as a result of partaking in regular resistance training exercise. The scientific evidence supporting the inclusion of resistance training as part of a healthy lifestyle is now indisputable. Whilst improvement of health is an obvious goal of many older athletes, it is the enhancement of sports performance that drives many in a quest to remain competitive, both against fellow competitors, but also – somewhat egocentrically – against their younger self. Even if you aren’t an elite masters athlete these benefits as outlined below can be truly life-changing.

Resistance training exercise remains an integral component of programs of most elite sportspeople. Increased maximal strength and power developed through the application of progressive resistance training has been shown to improve performance above and beyond that achieved by limiting training to sports specific training. This is now recognised by sports scientists, exercise physiologists, strength & conditioning experts and coaches.

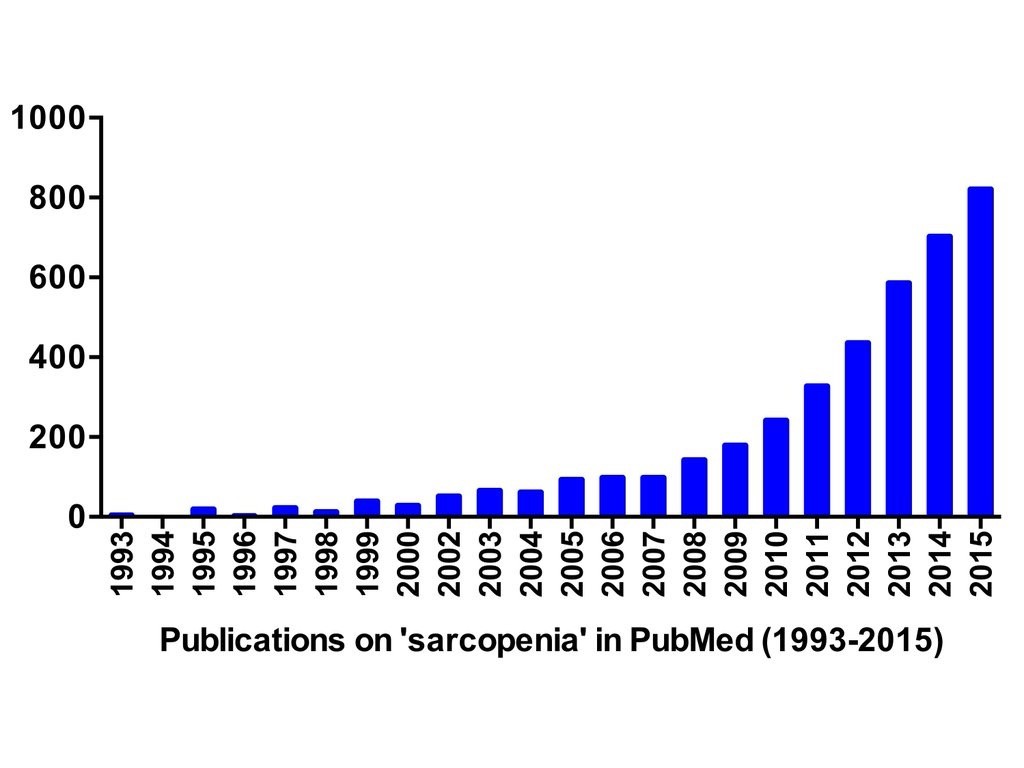

Of particular note for older athletes is that the performance benefits may be even greater than that of younger elite athletes. One of the hallmark changes to occur with age is the progressive loss of strength with significant atrophy or loss of skeletal muscle playing a significant role. This fundamental biological change that occurs with ageing manifests in a gradual deterioration of physical function and performance.

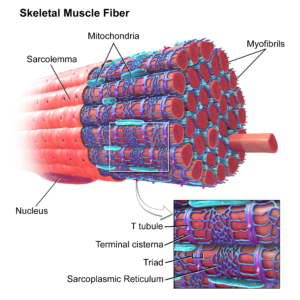

However, there is compelling evidence that the trajectory of this decline is modifiable and can be attenuated by lifestyle factors. The data to support regular exercise as a key factor in preserving skeletal muscle and physical function is overwhelming. Resistance training is one of the very best methods currently available for older adults and masters athletes to stimulate the physiological processes required to increase myofibrillar protein synthesis rates, skeletal muscle hypertrophy and muscular strength. These skeletal muscle adaptations lie at the core of why this type of exercise improves the functional performance of older adults and athletic performance of masters athletes.

The following 6 compelling reasons explain why resistance exercise should be included in all training programs of older adults where enhanced performance – for activities of daily living or sporting – are desired.

Enhance skeletal health. Stronger bones can handle greater training loads and transfer muscular forces more effectively and efficiently. Bone mineral density (BMD) decreases as we age however this can be slowed by regular physical activity and appropriate nutrition. Risk of musculoskeletal injury is increased when bone strength is decreased with age, especially during falls that can cause catastrophic consequences for some.

Resistance training has been shown to be quite a potent stimulus for improving bone mineral density. Some evidence suggests that plyometric-type or jumping activities also provide an excellent training method to stimulate significant and positive bone adaptation which yields increased BMD and therefore stronger bones.

Masters cyclists as a group are unfortunately at an elevated risk of reduced BMD (weaker bones) due to the non-weight bearing nature of cycling. It is strongly recommended that all masters cyclists – in fact, all cyclists – should perform adjunctive resistance exercise in their training program (see links 1, 2, 3, 4 & 5).

Maintain or increase lean body mass (skeletal muscle). Remember muscle is critical to both speed and endurance performance. From age 50 onwards muscle loss accelerates but there is a substantial amount of evidence that this is exacerbated by increased sedentarism (inactivity). Resistance training attenuates muscle mass loss.

Ageing is accompanied by reduced muscle mass and this has been mainly attributed to type II muscle fibre atrophy or reduction in size. It is unlikely that there is substantial muscle fibre loss however this remains to be elucidated. In older adults that have demonstrated substantial lean body mass loss and type II muscle fibre atrophy, prolonged resistance training has demonstrated significant increased muscle mass and this was shown to occur exclusively in type II muscle fibres. Nonetheless, some research has shown both type I and type II muscle fibre hypertrophy so more data is required to ascertain whether such things as age, gender, training status and training program parameters, affect muscle fibre changes and responsiveness to resistance training exercise (see links 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6).

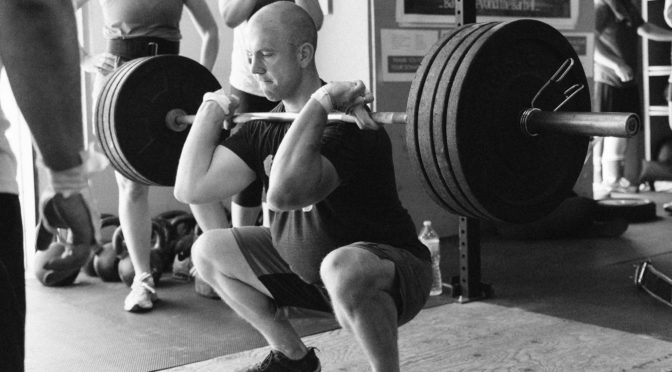

Increased muscular strength, power and speed. Research investigating the effects of progressive resistance training programs demonstrate that muscle strength, power and speed improve, and in many case, quite impressively. In fact, even in nonagenarians, skeletal muscle strength and functional mobility assessed by a gait velocity test improved dramatically (>170% and 48% increase, respectively) after only 8 weeks of resistance training.

As mentioned above, the significant atrophy that occurs with age in fast-twitch type II muscle fibres, directly impacts performance of activities that require speed. Resistance training can reverse some of this decline, restore some of the lost contractile protein of these critical muscle fibres, increase maximum skeletal muscle strength and therefore elicit substantial improvements in movement speed of various specific sporting skills.

Older athletes that are avoiding or not adjusting their program to allow a little time to perform some resistance training exercise are missing out on some incredible benefits (see links 1, 2, 3, 4, 5).

Lose body fat and get leaner. As outlined above, skeletal muscle mass decreases significantly from age 50 with concomitant decreases in resting metabolic rate (RMR). RMR is the largest component of total daily energy expenditure (TDEE) accounting for 60-80%. Whilst reductions in muscle mass account for a significant proportion of the accommodating changes in RMR, decreasing organ mass and decreases to specific metabolic rates of individual tissues also contribute to the decrease in RMR.

These age-related changes in RMR reduce TDEE. This may contribute to increased adiposity as we grow older given that energy intake to maintain body mass decreases proportionally to the degree of reduction in RMR and TDEE. In other words, if dietary habits and energy intake remains constant over time but RMR and TDEE decrease subsequent to the loss of skeletal muscle, positive energy balance may ensue and fat mass may therefore naturally increase.

Resistance training is well known for stimulating muscle hypertrophy or increasing skeletal muscle mass and has been shown to elicit reductions in fat mass in obesity during ad libitum diets. In contrast, aerobic exercise-induced weight loss consistently leads to reductions in lean body mass and RMR which may make the propensity of rebound fat gain more likely.

Inclusion of resistance training exercise in programs of older athletes or non-athletes doesn’t guarantee that there will be body fat loss (nutrition and diet obviously play a key role) but it certainly makes weight management easier and supports weight loss efforts if modifying the diet in an attempt to get leaner. Much of the research that has investigated the utility of resistance training in older adults demonstrates that it is a very effective fat loss strategy when performed with other lifestyle-based interventions aimed at improving physical function and body composition (see links 1, 2, 3, 4, 5).

Improves endurance. Resistance training that is designed to increase muscle strength and power has been shown to improve endurance performance. More evidence exists to support such exercise in younger adult athletes as there has been limited research exclusively focused on older athletes.

Nonetheless, the research completed to date is strongly suggestive that resistance training enhances endurance in older athletes and non-athletes. A study conducted in 2010 demonstrated that strength training consisting of 10 sets of 10 repetitions of 1RM load, 3 minutes rest between each set, 3 times/week, increased both knee extensor maximal voluntary contraction torque and cycling efficiency. It is reasonable to postulate that had they utilised a program that incorporated more compound, complex, multi-jointed exercises such as squats and deadlifts – such that all major lower body muscle groups were strengthened – significantly greater cycling economical benefit would have been elicited.

When masters endurance runners were studied after following a resistance training program designed to increase maximal strength (4 sets of 3-4 repetitions at 85-90% of 1RM, two times per week), a significant improvement in running economy at marathon pace (6.1%) and dynamic leg strength (16.3%) was achieved.

It is proposed that the following training adaptations may facilitate endurance performance improvement:

- the delayed use of the fast-twitch type II muscle fibers;

- enhanced neuromuscular efficiency;

- increased proportion of more fatigue-resistant fast-twitch type IIa fibres;

- improved musculo-tendinous stiffness (see links 1, 2, 3).

Reduce injury risk. Regularly performed resistance exercise can minimize the musculoskeletal alterations that occur during ageing. It may also contribute to the health and well-being of the older population.

There is strong evidence that suggests such exercise can prevent and control the development of several chronic musculoskeletal diseases. Improvement of physical fitness, function, and independence in older people, plus successful management of musculoskeletal disorders, results in dramatic improvements in quality of life.

Stronger muscles, bones, connective tissue, ligaments and tendons mean our limbs and joints are more able to handle the rigours of training, competing and activities of daily living (see links 1, 2, 3, 4, 5).

In conclusion, based on the 12 reasons that I have explored which demonstrate profound benefits to both the health, functional and sporting performance of older athletes and non-athletes, resistance training is a must-do and should be a pivotal component of any exercise program.

To read “12 reasons why older adults need to do resistance training exercise: part 1” that explores the health-related benefits in older adults see here.

For local Townsville residents interested in FitGreyStrong’s Exercise Physiology services or exercise programs designed to achieve the mentioned benefits or to enhance athletic performance, contact FitGreyStrong@outlook.com or phone 0499 846 955 for a confidential discussion.

For other Australian residents or oversees readers interested in our services, please see here.

Disclaimer: All contents of the FitGreyStrong website/blog are provided for information and education purposes only. Those interested in making changes to their exercise, lifestyle, dietary, supplement or medication regimens should consult a relevantly qualified and competent health care professional. Those who decide to apply or implement any of the information, advice, and/or recommendations on this website do so knowingly and at their own risk. The owner and any contributors to this site accept no responsibility or liability whatsoever for any harm caused, real or imagined, from the use or distribution of information found at FitGreyStrong. Please leave this site immediately if you, the reader, find any of these conditions not acceptable.

© FitGreyStrong