Several years ago researchers and authors Malhotra, Noakes & Phinney published an article in the British Journal of Sports Medicine titled:

“It is time to bust the myth of physical inactivity and obesity: you cannot outrun a bad diet” (see here)

This created quite a storm in several fields of scientific research including many fitness and nutrition blogs. It was lambasted by some though as inaccurate and misleading – just Google the title of the article and you’ll understand what I mean. Essentially, their article claimed that regular physical activity does not promote weight loss and that excessive consumption of carbohydrates, in particular, sugar, is the primary cause of the obesity epidemic. Whilst excessive sugar consumption has played an important role in exacerbating the obesity crisis, it would be naive and short-sighted to suggest that this is the be-all and end-all in explaining society’s current predicament.

More recently Julia Belluz and Javier Zarracina published (April 2016) an article at Vox titled:

“Why you shouldn’t exercise to lose weight, explained with 60+ studies” (see here)

This article posits that exercise is unhelpful for weight loss and makes very similar claims to the Malhotra et al. paper. Of course, the real question is, are these claims valid? Could it really be true that weight loss is not facilitated by increasing daily energy expenditure and exercise? I think the answer to these questions are not black or white. My main concern with the articles mentioned above is that they are rather myopic, polarising and do not provide a fair and balanced assessment of the current evidence.

Instead, the evidence published to date demonstrates that ‘our’ increasing waistlines are closely related – but not confined to – the interaction of the following 3 factors. Firstly, the sum total of all physical movement performed whilst awake has substantially decreased over the last 50 years. Secondly, activities of a sedentary nature have dramatically increased. What are you doing right now? Thirdly, total energy intake over the last 50 years has continued to increase over and above total daily energy expenditure requirements. If movement levels are low and energy intake high – irrespective of where the excess is derived from – body weight, body fat and BMI will naturally increase. But does increasing physical activity levels via a formalised exercise program and/or non-exercise based physical activities (e.g. leisure time movement, domestic chores/activities) facilitate weight loss by increasing total daily energy expenditure? The answer to this is yes and no.

Today I want to focus on the evidence that was accessible following a brief Google Scholar search that supports exercise as well as other non-exercise increases in daily physical movement as being promoters of weight loss. For anybody not familiar with Google Scholar (https://scholar.google.com.au), it is a search engine by Google that searches for only published, peer-reviewed journal-based research and consequently provides information that is evidence-based rather than ‘opinion-based’ which is largely what would be accessed via Google, Yahoo or any other search engine. So, what did I find?

One of the more interesting pieces of research that directly contradicts the article by Malhotra and co. is that written by Church et al. (2011). They concluded that over the last 50 years in the U.S., daily occupation-related energy expenditure was estimated to have decreased by more than 100 calories per day, and this reduction in energy expenditure could account for a significant portion of the increase in mean U.S. body weights for women and men. What this would suggest is that rather than increased obesity rates being caused exclusively by too many carbs or too much sugar, as argued by the “you can’t outrun a bad diet” article, the current problem has been driven by large reductions in energy expenditure due to changes to occupation-related physical movement. In other words, we have transitioned from jobs that are active and require a lot of physical movement to jobs now that have most of us sitting on our backsides for hours on end.

Previous reports based on estimated caloric consumption from food production and food disappearance (food waste) estimates have concluded that increased caloric consumption could account for most, if not all, of the weight gained at a population level in the U.S. Nonetheless, a recently validated differential equation model was used to identify a conservative lower bound for the amount of food waste in the U.S. (Hall et al. 2009). This analysis determined that prior estimates of national food waste were grossly underestimated; indicating that the national average caloric intake was much lower than previously estimated. As such, these results and those of Church imply that increased caloric intake or for that matter, increased sugar consumption, cannot solely account for the observed trends in national weight gain in the US.

The following is a summary of some of the research that has been published investigating whether obesity is related to physical inactivity and what effect increased physical activity has on obesity risk and management.

1. Banks et al. (2010) reported that: “Obesity increases with increasing screen-time, independent of purposeful physical activity.”

2. Goodpaster et al. (2010) found that: “Among patients with severe obesity, a lifestyle intervention involving diet combined with initial or delayed initiation of physical activity resulted in clinically significant weight loss and favourable changes in cardiometabolic risk factors.” In the group where physical activity was delayed, the addition of such physical activity promoted greater reductions in waist circumference and hepatic fat content.

3. Banks et al. (2011) showed that: “Domestic activities and sedentary behaviours are important in relation to obesity in Thailand, independent of exercise-related physical activity. In this setting, programs to prevent and treat obesity through increasing general physical activity need to consider overall energy expenditure and address a wide range of low-intensity high-volume activities in order to be effective.”

4. Villareal et al. (2011) demonstrated that: “…in obese older adults a combination of weight loss and exercise provides greater improvement in physical function than either intervention alone.”

5. McGuire & Ross (2012) reported that: “…light physical activity, incidental physical activity and sedentary behaviour were not associated with abdominal obesity amongst inactive men and women whereas moderate-to-vigourous physical activity predicted lower visceral adipose tissue.”

6. The study by Fan et al. (2013) was: “…to test if moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) in less than the recommended ≥10-minute bouts related to weight outcomes.” Both higher-intensity short bouts and long bouts of physical activity related to lower BMI and risk of overweight/obesity whereas neither lower-intensity short bouts nor long bouts related to BMI or risk of overweight/obesity. They concluded that: “The current ≥10-minute MVPA bouts guideline was based on health benefits other than weight outcomes. Our findings showed that for weight gain prevention, accumulated higher-intensity PA bouts of <10 minutes are highly beneficial, supporting the public health promotion message that ‘every minute counts’.”

7. Cleland et al. (2014) found that: “High sitting and low activity increased obesity odds among adults. Irrespective of sitting, men with low step counts had increased odds of obesity. The findings highlight the importance of engaging in physical activity and limiting sitting.”

8. Jakicic et al. (2014) concluded that moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA > 10) of 200-300 min per week, coupled with increased amounts of low-intensity physical activity (LPA), are associated with improved long-term weight loss. Interventions should promote engagement in these amounts and types of physical activity.

9. Murabito et al. (2015) discovered that moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) as measured by accelerometry was associated with less visceral adipose tissue (VAT) and subcutaneous adipose tissue (SAT) and better fat quality as assessed by multi-detector computed tomography. With increasing MVPA, there was a concomitant decrease in VAT. Higher levels of MVPA were associated with higher SAT fat quality, even after adjustment for SAT volume. They concluded that:

“MVPA was associated with less VAT and SAT and better fat quality.”

10. Mekary et al (2015) reported that: “….over 12 years long-term weight training is associated with less waist circumference increase, whilst moderate-to-vigorous aerobic activity was associated with less body weight gain in healthy men.”

11. Hume et al. (2016) concluded that: “….counter to the energy surfeit model of obesity, results suggest that increasing energy expenditure may be more effective for reducing body fat than caloric restriction, which is currently the treatment of choice for obesity.”

12. Myers et al. (2016) suggests that there exists clear associations among objective measures of physical activity, sedentary behaviour, energy expenditure, adiposity and appetite control. They produced data that indicates strong links between physical inactivity and obesity with this relationship likely to be bidirectional.

13. Wu et al. (2017) tested 12-weeks of low- and high-intensity exercise training in Mexican-American and Korean premenopausal overweight/obese women. Results showed that such exercise reduced body mass index, body fat percentage, fat mass and visceral adipose tissue with concurrent increases in lean mass.

14. Quist et al. (2018) examined the effects of 6-months of active commuting and leisure-time exercise on fat loss in women and men who were overweight or obese. Clinically meaningful fat loss of over 4 kilograms was elicited. Vigorous intensity exercise was shown to be more effective in reducing body fat versus moderate intensity exercise.

15. Stoner et al. (2019) concluded that the findings of their meta-regression “lend support to the use of exercise prescription for promoting weight loss and improving health outcomes in adolescents with overweight/obesity.”

16. Zhang et al. (2020) found that 12-weeks of intense exercise (without concurrent nutritional intervention, i.e. ‘put on a diet’) significantly improved cardiometabolic parameters (i.e. fasting blood glucose) and decreased weight, total percent body fat, whole-body fat mass, android, gynoid, and trunk fat mass, abdominal subcutaneous fat and abdominal visceral fat. Reductions of over 15 cm² of abdominal visceral fat were achieved in just 3 months!

17. Berge et al. (2021) produced clinically significant weight loss in people with severe obesity despite the study having no specific focus on body weight reduction. The group that performed moderate‐intensity continuous training combined with high‐intensity interval training lost an average of 5 kilograms in 24-weeks.

What does this research tell us?

Quite a lot I would say. Of particular note is that this only represents a very small sample of the evidence that directly counters the claim that widespread societal levels of physical inactivity have little to do with burgeoning obesity rates. What is more, it crystallizes just how contentious Malhotra, Noakes & Phinney’s editorial was. Exclusively assigning blame for the obesity epidemic to the excessive intake of sugar is not supported, I believe, by the current evidence. The dramatic reductions in the sum total of all physical activity accumulated during the day appears to account for a substantial amount of the increased weight seen in recent decades.

Firstly, there is a substantial amount of research which demonstrates that sedentary behaviours, sitting time and low physical activity levels manifestly increase one’s risk of becoming overweight or obese. Secondly, moderate-to-vigourous physical activity compared to light physical activity has been shown to be associated with less visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissue, impacts positive effects on fat quality, is related to lower BMI, lowers risk of overweight/obesity, prevents weight gain following weight loss, promotes greater reductions in waist circumference and produces favourable changes in cardio-metabolic risk factors.

So to conclude, my Google Scholar search unveiled that there is a large body of evidence that demonstrates that there may be no myth to bust regarding obesity and physical inactivity or foundation to suggesting that physical activity plays no role toward promoting weight loss. Others have been critical of this line of thinking too, in particular Dr Steven Blair, so I would suggest that if you wanted to read further on this here would be a good place to start.

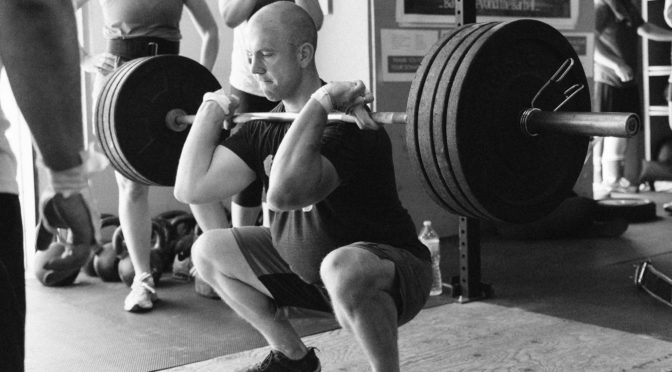

My next article will explore the evidence that exercise does not assist weight loss in all exercisers due to various compensatory mechanisms (see here). Until then, stay active, keep moving and don’t forget to include some resistance exercise in your week.

For local Townsville residents interested in FitGreyStrong’s Exercise Physiology services or exercise programs designed to improve health, physical function and quality of life or to enhance athletic performance, contact FitGreyStrong@outlook.com or phone 0499 846 955 for a confidential discussion.

For other Australian residents or oversees readers interested in our services, please see here.