What are they:

- Increases longevity and improves quality of life

- Helps manage hypertension and decreases heart disease

- Enhances sleep quality and quantity

- Prevents/treats type 2 diabetes & decreases inflammation

- Prevents cognitive decline & neurodegenerative disease

- Improves mental health

- Enhances skeletal health

- Maintains or increases lean body mass (muscle)

- Increases strength, power, speed and physical function

- Reduces body fat and help maintain body fat loss

- Improves endurance performance

- Reduces injury risk

Resistance or weight training is a critical component of training programs of most elite athletes irrespective of the sport. The benefits of resistance training – to increase maximal muscle strength and neuromuscular power – has long been recognised by most strength and conditioning experts, coaches and sport scientists as key to sporting performance. Logic would dictate therefore that if elite athletes are doing concurrent training to improve sport specific performance, masters athletes may also reap huge benefits too. There is now compelling evidence to suggest that resistance training can potentially augment athleticism of masters athletes well beyond that achieved by confining training to sports specific training. Furthermore, these significant benefits are not just limited to sprint, speed or power orientated sports but endurance performance may also be enhanced.

However, before I address the athletic performance benefits of resistance training for older athletes and functional enhancement such exercise has in older non-athletes (these will be outlined in part 2), I want to discuss the significant and sometimes life-changing health benefits that have been well documented in research conducted over the last 20 years. There is a great deal of data now to support the use of resistance training to help treat and manage a number of chronic diseases that become more prevalent as we get older. The following outlines 6 key reasons why resistance training exercise should be included in all programs of older athletes and exercise programs of older non-athletes.

Reduce the risk of death. Evidence continues to accumulate to show that skeletal muscle strength is strongly predictive of longevity. Maximum muscle force in men aged 20-80 is independently and inversely associated with all-cause mortality. Over the age of 60 years, all cause and cancer-associated mortality is twice as likely in individuals with low compared to high skeletal muscle strength. Older adults over 15 years who reported twice/weekly strength training had 46% lower odds of all-cause mortality than those who did not. Resistance training when performed regularly is one of the best methods to increase skeletal muscle strength (see links 1, 2, 3, 4). A recent assessment of the research that has been conducted in older adults showed that resistance training substantially improved health-related quality of life. In other words, resistance training and getting stronger has a direct impact on our perception of how meaningful, manageable and comprehensible life is, and as such, significantly greater promotion of this type of activity is warranted (see here).

Helps manage hypertension and decrease heart disease. High blood pressure can still affect masters athletes and resistance training when performed in conjunction with aerobic or endurance training has been shown to have a positive effect and reduce blood pressure. However, data to support resistance training as a stand alone practice is mixed with some studies suggesting improvement in systolic and diastolic blood pressure versus other research that has shown such exercise can increase arterial stiffness. Evidence tends to point to concurrent exercise (resistance training combined with aerobic exercise) as being the most effective for reducing the risk of heart disease (see links 1, 2, 3, 4).

Improves sleep quality and quantity. Problems with sleep are common with advancing years and occur in over half of adults age 65 and older. It has been estimated that insomnia affects about a third of the older population. The evidence to date suggests that poor sleep hygiene directly impacts and worsens many aspects of health including such things as mental health, obesity, heart disease, cognition, memory, executive function, metabolic disturbance and falls to name just a few.

Overall quality of life is thus dramatically reduced. Other factors associated with ageing, such as disease, changes in environment, or concurrent age-related processes also may contribute to problems of sleep. Sleep disturbance and long sleep duration, but not short sleep duration, have been shown to be associated with increases in markers of systemic inflammation. Research has shown that both sleep quality and quantity is improved with increased levels of exercise. Resistance training alone appears to positively impact sleep quality but more data is required to confirm that sleep quantity is equally improved (see links 1, 2, 3).

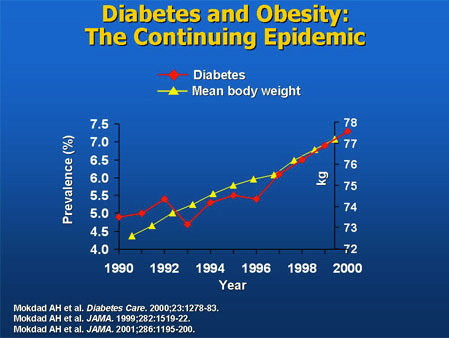

Prevent/treat type 2 diabetes & decrease inflammation. Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is one of the fastest growing non-communicable diseases worldwide and occurs much more frequently in those that are overweight and obese. However, impaired blood glucose metabolism, one of the hallmarks of T2DM, is an increasingly common problem in those that are not overweight and have relatively normal BMI. A poor and overindulgent diet – high in things like sugar, trans-fats, processed foods, junk foods and that are low in fish (omega-3 fatty acids), vegetables, fruit, fibre and high quality protein – combined with long-term sedentarism has been postulated as playing a leading causative role. Such a combination causes the development of chronic positive energy balance whereby excess energy disposal and adipose storage triggers a significant oxidative pro-inflammatory response referred to as metabolic inflammation.

In obesity, expanding adipose tissue attracts immune cells creating an inflammatory environment within this fatty acid storage organ. Skeletal muscle is the predominant site of insulin-mediated glucose uptake and insulin resistance is considered the primary defect that is evident years before the development of T2DM. Resistance training has consistently been shown to improve the ability of the skeletal muscles to take up and metabolise blood glucose (sugar) and is therefore an important strategy in managing T2DM. Finally, there is now scientific data to show that disorders that arise and are linked to inflammation (e.g. Insulin resistance, obesity, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, cancer, chronic kidney disease, osteoarthritis, Alzheimer’s disease and many more), can be improved or mitigated with resistance training and exercise (see links 1, 2, 3, 4, 5).

Prevent cognitive decline & neurodegenerative disease Recent research has shown that long-term resistance training in older women promotes executive function, memory, reduced cortical white matter atrophy and increased peak muscle power. Such findings are very exciting as they suggest that exercise and resistance training can modify brain neuroplasticity and help improve brain function. The current thinking is that resistance and physical exercise represents a promising nonpharmaceutical intervention to prevent age-related cognitive decline and neurodegenerative diseases such as dementia and Alzheimers. There is some evidence that the mechanisms behind these alterations may be related to increased levels of Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and IGF-1. BDNF-induced neuroplasticity is speculated to be facilitated by physical exercise but conclusive evidence supporting this mechanism of action has not yet been established (see links 1, 2, 3, 4).

Improved mental health. There is substantial evidence to demonstrate that resistance training and exercise more generally has a very dramatic and potent effect on improving mental health and treating those that suffer from mental health disorders. For example, research has shown that high-intensity resistance training is more effective than low-intensity resistance training or standard care by a GP in the treatment of depression in older patients. Resistance exercise has also be shown to reduce anxiety, slow the progression of white matter lesions in older women, improve symptomatology and disease severity in severe mental illness and essentially improve overall quality of life and general mental health (see links 1, 2, 3).

To finish up I cannot emphasise enough just how important resistance training exercise is for all older adults including masters athletes. The reasons mentioned above are only some of the many that support resistance training exercise as an essential ingredient of a healthy lifestyle and confirm current recommendations for people to partake in a minimum of 2 resistance training sessions per week.

To read part 2 of “12 reasons why older adults need to do resistance training exercise” which discusses the performance-enhancing benefits for older athletes and the incredible functional improvements that can be achieved in older non-athletes, see here.

For local Townsville residents interested in FitGreyStrong’s Exercise Physiology services or exercise programs designed to achieve the above-mentioned benefits or to enhance athletic performance, contact FitGreyStrong@outlook.com or phone 0499 846 955 for a confidential discussion.

For other Australian residents or oversees readers interested in our services, please see here.

Disclaimer: All contents of the FitGreyStrong website/blog are provided for information and education purposes only. Those interested in making changes to their exercise, lifestyle, dietary, supplement or medication regimens should consult a relevantly qualified and competent health care professional. Those who decide to apply or implement any of the information, advice, and/or recommendations on this website do so knowingly and at their own risk. The owner and any contributors to this site accept no responsibility or liability whatsoever for any harm caused, real or imagined, from the use or distribution of information found at FitGreyStrong. Please leave this site immediately if you, the reader, find any of these conditions not acceptable.