In part 1 of “The Ebbeling vs. Hall trials: Re-visiting How Diet Affect Energy Expenditure & Weight Loss” I argued that the conclusions made by authors of the Ebbeling trial – where it was purported that a very low carbohydrate diet significantly mitigated the reduction in energy expenditure subsequent to weight loss compared to diets higher in carbohydrates – were flawed. As stated previously: “The variability in the individual data for diet type and their effect on energy expenditure is discordant to that of the pooled data thus invalidating the generalisability of the results. To truly make the claim that a novel bio-effect exists for a particular diet type, a consistent, reliable pattern of response should be reproducible in a majority of people.”

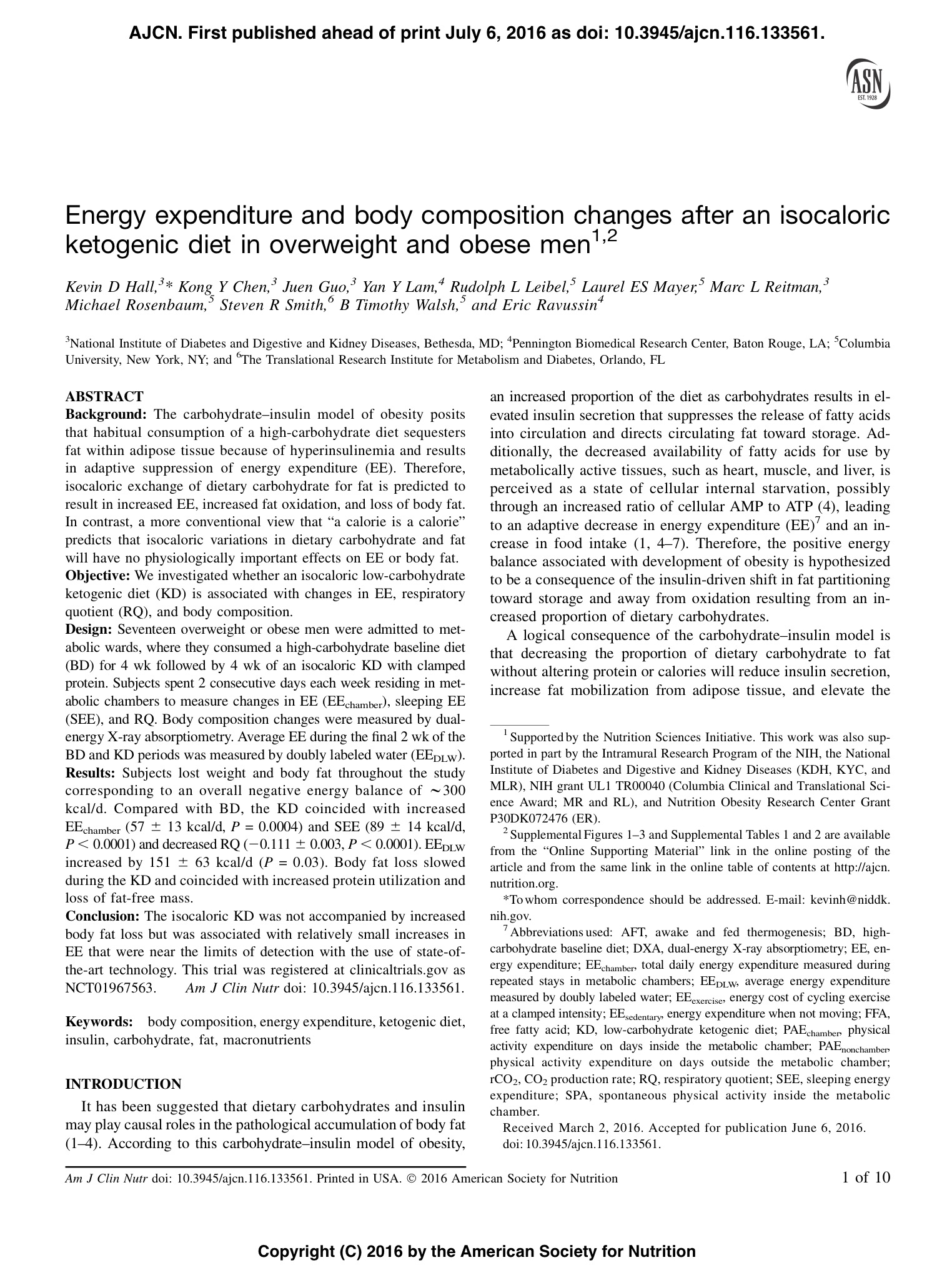

In part 2 I want to take a closer look at the results of the study headed up by Dr Hall titled: “Energy expenditure and body composition changes after an isocaloric ketogenic diet in overweight and obese men” that was published in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. This study was designed to test the merits of the carbohydrate-insulin model of obesity. As mentioned in part 1, a number of unique claims that underpin this model are made by those advocating very low carbohydrate (VLC) diets. Firstly, that by decreasing the proportion of carbohydrate in the diet a concomitant reduction of insulinemia will ensue, and in so doing, cause increased fat mobilisation from the adipose tissue thus causing a greater oxidation of circulating free fatty acids (FFAs). Insulin is viewed in this context as the ‘gate-keeper’ of whether fat is partitioned toward storage (higher insulin) or mobilised and oxidised for energy metabolism (lower insulin). Secondly, as a consequence of reduced insulin secretion and increased availability of FFAs for use by metabolically active tissue, VLC or ketogenic diets will disproportionately increase energy expenditure compared to isoenergetically-matched higher/high carbohydrate (HC) diets. Thirdly, it is concluded that ‘a calorie is not a calorie’ therefore, because energy expenditure and body fat metabolism will be impacted differentially and advantageously by exchanging an isoenergetic amount of dietary carbohydrate for fat.

Hall and 10 of his colleagues (see page title below) essentially concluded that a VLC diet was no more effective compared to a HC diet for reducing body fat. Small increases were detected in energy expenditure for the VLC diet but this was dismissed as clinically irrelevant. The publication of these findings were greeted with an incredible range of reactions ranging from the “I-told-you-so” piece by Anthony Colpo, the excellent analysis by Stephan Guyenet, to the cringe worthy blog of Jason Fung. Indeed, many noses were put out of joint and so dismayed were some, that the rebuttals transcended professional criticism with personal attacks and slurs directed at Kevin Hall himself. What I find most perplexing about this whole thing is that the results of Hall’s trial are some of the most damaging findings to date and provide no support for the carbohydrate-insulin model of obesity.

The results of this study were presented by Kevin Hall at the 2016 World Obesity Federation meeting. He was interviewed during this conference by Yoni Freedhoff (see @YoniFreedhoff on Twitter), a Medical Practitioner and Obesity Specialist from Canada and this was uploaded to YouTube. To cut a long story short, when questioned about his study, Hall claimed that the carbohydrate-insulin theory of obesity had been debunked, with no substantial differences in fat loss between a VLC or HC diet. And whilst energy expenditure had initially increased on the VLC diet, it was a transient change that subsequently decreased linearly over time amounting to nothing clinically relevant (see the interview below).

Following upload of this video to YouTube the Internet went into meltdown with Twitter specifically ablaze with discussion and fierce debate about what it was exactly that Kevin Hall’s study had actually demonstrated – here is just one example of the fascinating discussion that occurred on Twitter following publication of this trial. There was little to go on apart from the above video, some commentary, some graphs and the poster of the study.

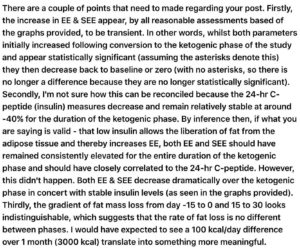

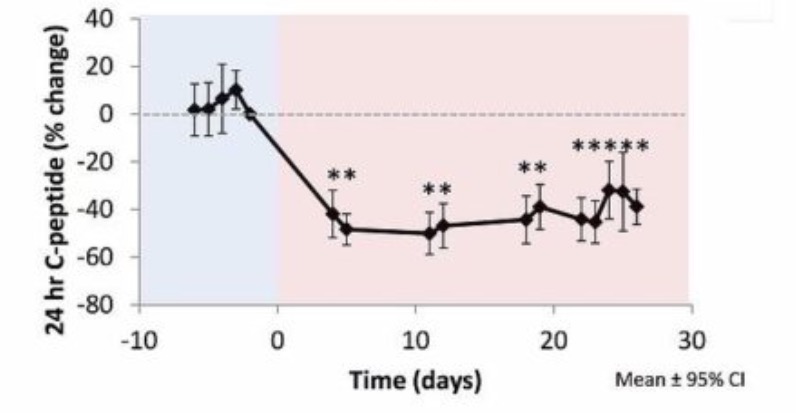

First off the ranks to take aim at this study was Dr Michael Eades, author of Protein Power and his blog of the same name. Eades was applauded far and wide by many on social media as debunking the debunker. After reading his blog, though, it was apparent that there were several flaws in his logic and I subsequently made these comments . My key concerns were, firstly, that there was no effort to appropriately explain why there was no relationship found between the rate of fat loss and 24-hour C-peptide levels (insulin), given that the carbohydrate-insulin model of obesity predicates that lipolysis is inversely proportionately to insulin production and therefore as insulin levels decrease, fat loss should increase. Secondly, there was no acknowledgment that total daily energy expenditure (EE) actually returned back to baseline over the duration of the VLC diet, even though insulin levels remained consistently depressed for the entire VLC diet phase. Given that insulin levels decreased and remained as such following the switch from the HC to VLC diet, it is completely reasonable to expect that EE would remain consistently elevated too if the carbohydrate-insulin model is sound. This simply did not happen and both these findings are monumentally difficult to account for as they completely contradict what would be predicted and expected to occur based on this model.

I had intended, in this blog, to explore and make further comment on some more of the reactions following full publication of this trial, but you’ll have to wait until part 3 of this series as I have decided to dedicate a whole article to that as there is a lot to comment on.

Results published

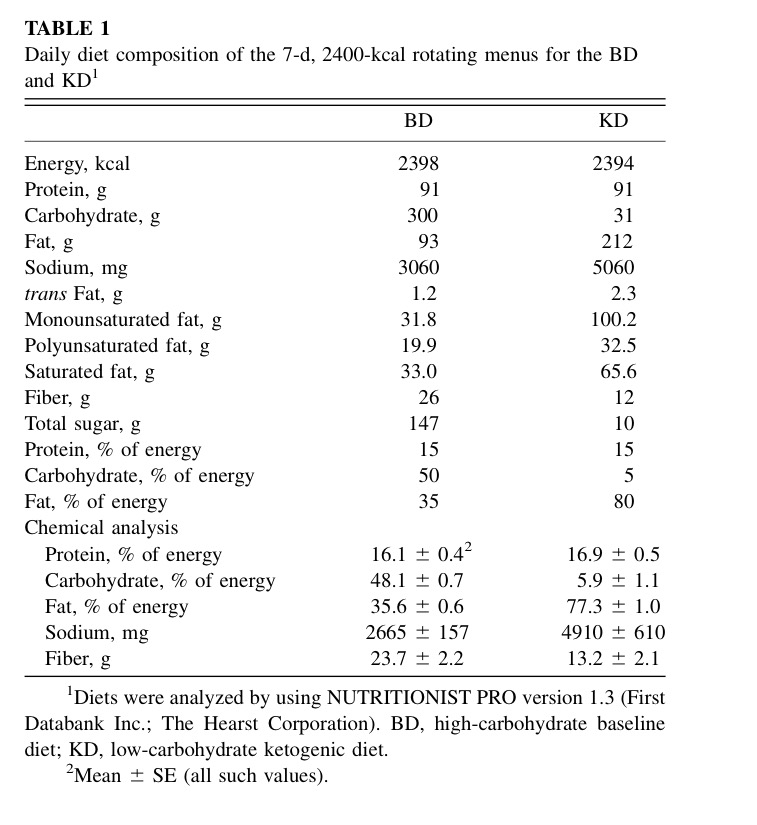

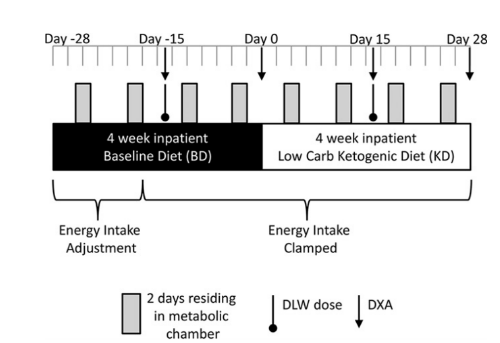

The paper was finally published ahead of print July 6th 2016. Kevin Hall’s research group in summary took 17 overweight or obese men and confined them to metabolic wards where they consumed a HC (also high in sugar) for a 28 day run-in period followed by an isoenergetic VLC diet for an additional 28 days. All foods and beverages were provided to the participants and food outside of that on the menu plans was prohibited (this was strictly enforced). Dietary protein was clamped at approximately 16% for the entire duration of the study for both phases. The diets were structured with the intention that energy balance was achieved with sufficient energy intake to maintain participant’s body weight. Daily diet composition of the 7-day, 2400 kcal rotating menus for the VLC and HC diets is shown below.

Subjects were prescribed 90 min (3 x 30 mins blocks) of daily stationary cycling at a clamped intensity. The intensity of the cycling exercise was determined during the third screening visit. Two 30 minute bouts of stationary bicycling at a fixed speed and resistance with a HR greater than 0.3×(220-age-HRrest)+HRrest but not exceeding 0.6×(220-age-HRrest)+HRrest and no signs of arrhythmia. The initial speed and intensity was set to that of the second screening visit and adjusted to stay within target HR during the second 30 minute bout of cycling. The speed and intensity of the stationary cycling determined during the third screening visit was to be repeated on days of scheduled cycling exercise during the inpatient visit to total 90 minutes per day. Overall physical activity was quantified with small, portable, pager-type accelerometers.

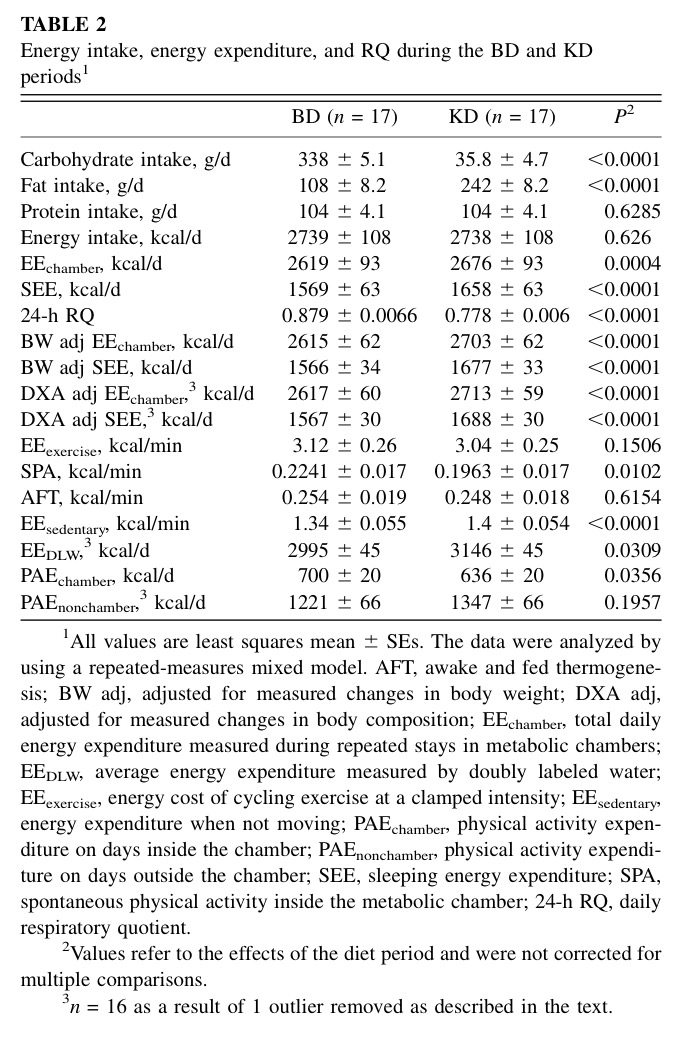

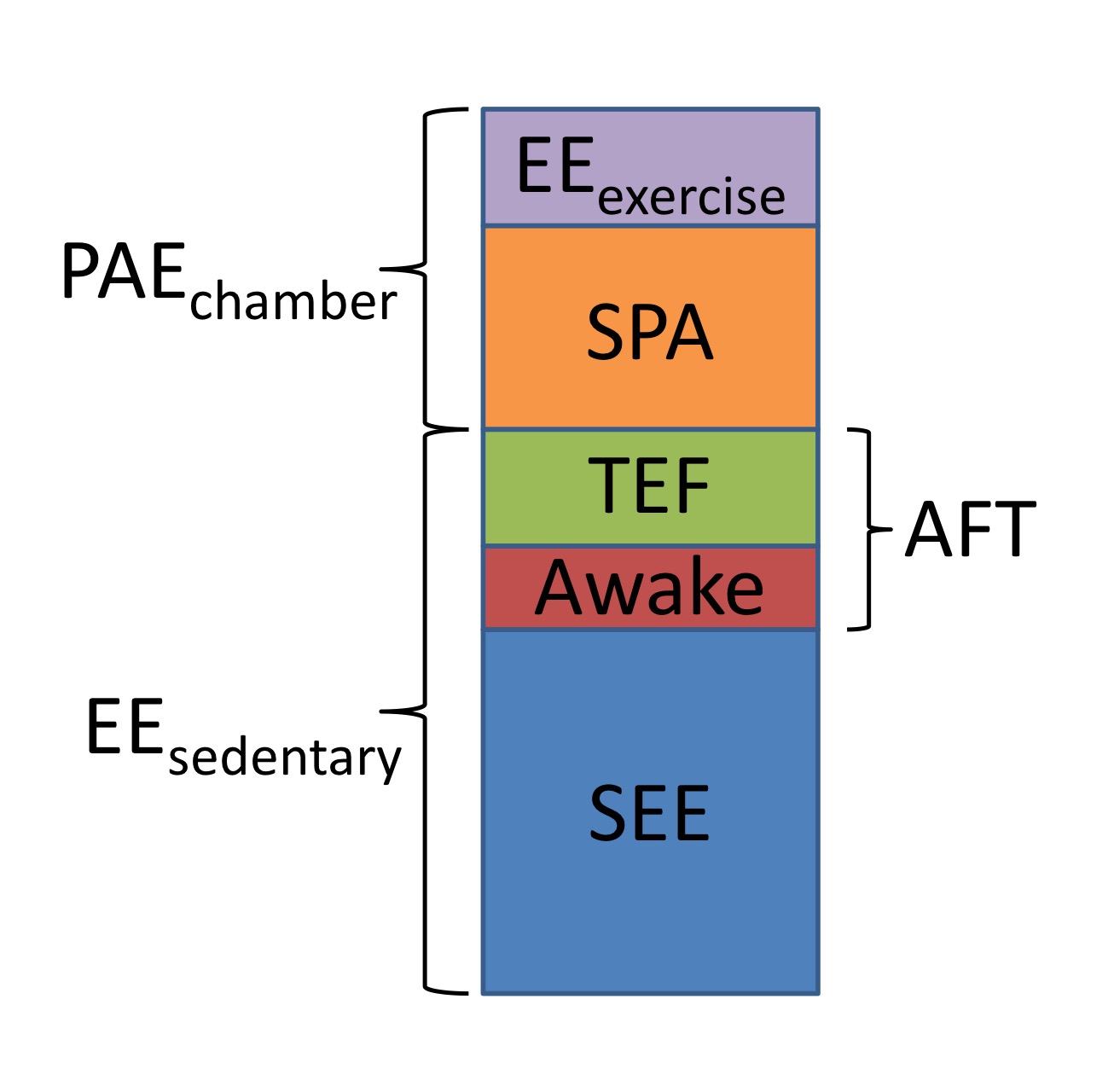

Two consecutive days each week were spent residing in metabolic chambers to measure total daily energy expenditure, respiratory quotient and sleeping energy expenditure (SEE). Body composition was assessed by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) and the average EE during the last 2 weeks of each diet was assessed by the doubly-labeled water (DLW) technique.

Other parameters assessed were daily respiratory quotient (24-h RQ), energy cost of cycling exercise at a clamped intensity (EEexercise), energy expenditure when not moving (EEsedentary), physical activity expenditure on days inside the chamber (PAEchamber), physical activity expenditure on days outside the chamber (PAEnonchamber), spontaneous physical activity inside the metabolic chamber (SPA). Relevant blood and urinary biomarkers measured included insulin, C-peptide, urea, ammonia, creatinine, thyroid hormones, nitrogen, ketones, adrenalin and norepinephrine. The daily diet composition is outlined below.

Primary endpoints were changes in EE (total and sleeping) and 24-hr respiratory quotient, and secondary endpoint was changes in body composition.

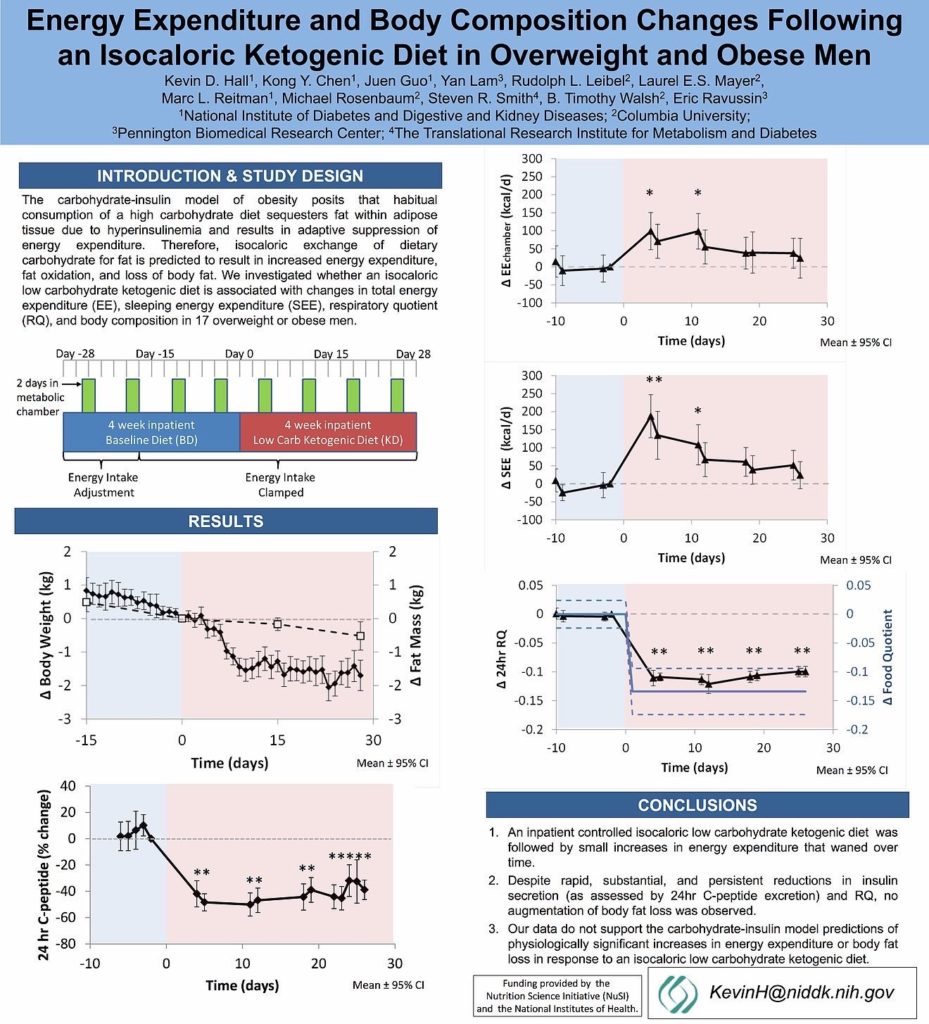

The key findings of this study in relation to the primary and secondary endpoints were:

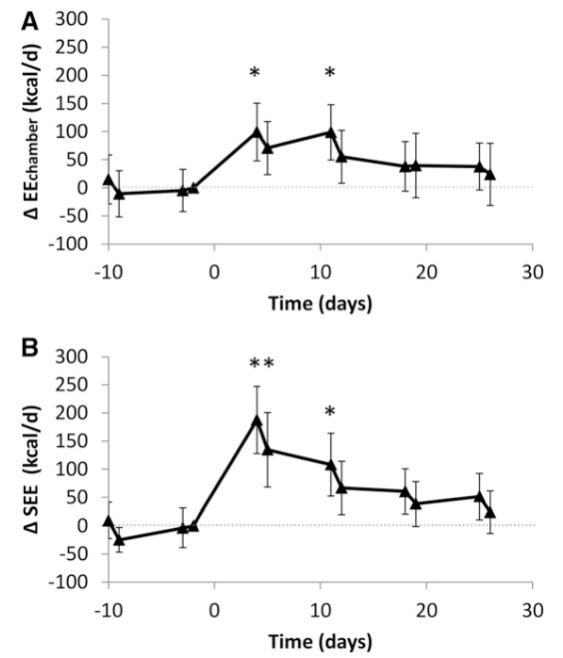

- EE during the VLC phase was 57 ± 13 kcal/d greater than during the HC period.

- Adjusting total EE data for body composition changes resulted in the VLC diet period having 96 ± 12 kcal/d greater expenditure than the HC diet period.

- SEE during the VLC phase was 89 ± 14 kcal/d greater than during the HC period.

- Adjusting SEE for body composition changes resulted in the VLC diet period having 121 ± 13 kcal/d greater expenditure than the HC diet period.

- There was a significant linear decrease over time in EE and SEE following the initial increases outlined above and this occurred irrespective following adjustment for changes in body weight and body composition.

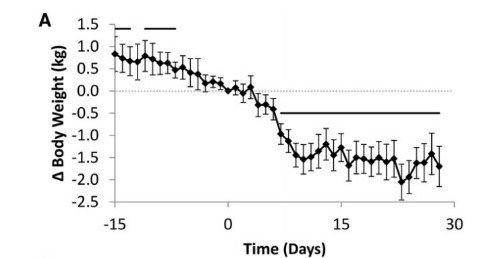

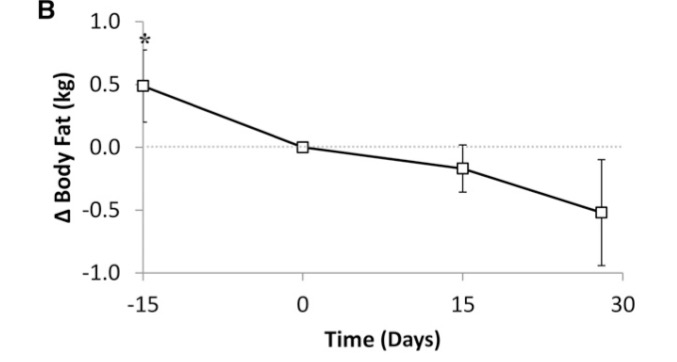

- The VLC diet resulted in a slowing or blunting of fat loss versus the HC diet (-0.5 kg in 28 days for VLC vs. -0.5 kg in 14 days for HC).

- Following transition to the VLC diet, the loss of fat mass in the subsequent 14 days was not statistically significant.

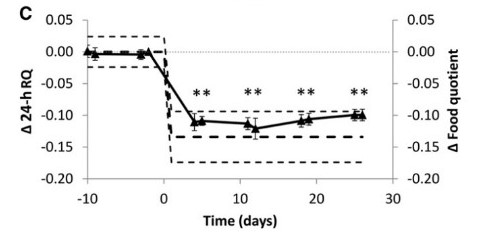

- Respiratory quotient (24-h RQ) decreased significantly from approximately 0.88 during the HC period to 0.78 at the start of the VLC period and remained approximately constant until the end of the study, indicating a rapid and persistent increase in fat oxidation.

Comments and Analysis

It is important at this juncture to state the obvious here but which ironically seems to have been missed by those that have cast aspersions on Kevin Hall. This study was intended to answer the questions as to whether the lowering of insulin levels via an isoenergetic dietary exchange from HC to VLC, translated into: 1) A disproportionate increase in EE and; 2) Greater loss of body fat. From what I can gather his recent work has aimed to uncover the perennial and mechanistic question of whether greater energy expenditure and fat loss can be achieved by altering the proportion of carbohydrates in isoenergtically macronutrient manipulated protein-clamped diets. These are important questions to answer because increased EE and body fat loss – simply induced by decreasing the proportion of carbohydrates for a given isocaloric diet – would have major implications in the treatment of obesity. As such, energy intake and protein were clamped so that the effect of dietary carbohydrate restriction could be isolated as the independent variable with EE and fat loss dependent variables.

This study was not, however, designed to answer the questions as to whether dietary carbohydrate restriction decreases ad libitum energy intake through enhanced appetite satiety – which could account for the efficacy of VLC diets in altering body composition – or whether such restriction generates greater improvements in metabolic health in those suffering from obesity or disorders such as type-2 diabetes. Those claiming, then, that Hall and co are misrepresenting, misconstruing or ‘spinning’ the data of this study – to either “protect one’s reputation”, or perpetuate some sort of “government and industry conspiracy” to maintain the “high carbohydrate diet status quo” and thereby place “people’s health and wellbeing at risk” – are preposterous and offensive. I see no evidence whatsoever that Hall et al. are advocating high sugar, high carbohydrate diets for those suffering from obesity and other metabolic disorders or conditions.

Energy Expenditure

At face value and in support of the argument that VLC diets provide a “metabolic advantage”, adjusting total EE data for body composition changes resulted in the VLC diet period having 96±12 kcal/d greater expenditure than the HC diet period. If we base our conclusions on this figure alone, we should be able to say that this study supports the existence of a “metabolic advantage” that could potentially be harnessed to facilitate obesity treatment. And this is precisely what was latched on to by the VLC diet advocates. In my opinion, however, this does not adequately contextualise the temporality of the EE data and, as such, obfuscates a more nuanced interpretation of what the results show. Let’s take a look at figure 3A and 3B from the trial that track both EE and SEE.

If you eyeball and track EE/day over time in figure 3A, the trajectory of decline from ∼day 10 to endpoint, is ∼100 kcal/day to ∼20 kcal/day, respectively. For figure 3B, the decline is even greater. SEE peaks at ∼200 kcal/day around day 4 and tanks, decreasing to ∼20 kcal/day by endpoint. Therefore, in support of the argument against any sort of “metabolic advantage” of VLC diets, this waning of total EE clearly shows that no clinical difference exists given that:

- By ∼day 12 and thereafter EE and SEE for the VLC diet are not statistically significant versus the HC diet.

- 95% confidence interval for the VLC diet by ∼day 18 contains zero with no statistically significant difference for EE or SEE.

Thus, we should accept the null hypothesis as there is no difference between the HC and VLC diets.

The trajectory of EE and SEE in the VLC diet and waning and return back to baseline demonstrates that these metabolic changes were acute and transient. Whilst I do not want to speculate as to the reasons why, it is fascinating that these findings – that are as clear as the light of day – were either ignored, dismissed or not understood by those endorsing the idea that VLC diets provide a “metabolic advantage”. Interestingly, Hall’s is not the only study to show the phenomena of “adaptive” thermogenesis, as discussed by the POUNDS lost study, where resting energy expenditure (REE) is indeed adaptive over time. Both body weight and REE decreased by 6 months, but were unaffected by diet composition.

Lastly, body composition-adjusted EE would have been overestimated given that such adjustment was not able to discern that much of the weight reduction following transition to the VLC diet came from water losses and not metabolically active tissues. In short term studies investigating VLC diets you will see larger initial decreases in body weight compared to diets higher in carbohydrates due to potassium deficits and the reduction of muscle (water-laden) glycogen as described by Kreitzman et al (1992). The additional data below showing an initial increase in protein utilisation and metabolism, and concomitant blunting in fat loss provides further support for this.

Hall’s data, therefore, strongly indicates that there is no chronic, persistent and clinically relevant elevation of EE and SEE with VLC diets when compared to isocaloric HC diets. As discussed by Hall and co, other controlled, inpatient isocaloric feeding studies where dietary protein is held steady, demonstrate that varying carbohydrates from 20% to 75% of total calories found either small decreases in EE or no significant differences with carbohydrate restriction. Taken together, it would appear that dietary carbohydrate restriction as low as 20% fails to elicit any noteworthy changes in EE, but further restriction to a level where carbohydrates supply 5% of total calories results in slight but transient increases in EE and SEE. It should be acknowledged that the study authors anticipated this slight (initial) increase and the results confirm their mathematical model simulations. Such increases seem to be part of an “adaptive” thermogenic response where an increased shift toward ketogenesis is required, but which probably subsides once gluconeogenesis declines following the brain’s shift away from glucose toward ketone oxidation.

Body Composition

Unintentional weight and fat loss occurred throughout the study and indicated an overall state of negative energy balance. Negative energy balance during the last 2 weeks of the HC and VLC diet periods were not significantly different whether assessed by the measured DXA body composition changes or by calculating energy intake minus expenditure as measured by DLW. However, following transition to the VLC diet, fat loss actually slowed (see below). Moreover, 95% confidence intervals (day 28 of the VLC diet) lends support to this, with the lower range of the interval for body fat loss encroaching upon zero.

Even if we grant that most of this slowing in fat loss was confined to the first 15 days following transition to the VLC diet, the rate of loss from days 15-30 remained constrained in comparison to that seen in the HC diet (VLC -0.3 kg vs HC -0.5 kg). This occurred despite daily fat oxidation adapting completely within the first week of the VLC diet, as shown by the rapid and sustained maximal drop in respiratory quotient seen by day 4 (depicted in figure 3C below). Such data illustrates that daily fat oxidation adapts very quickly and completely when dietary carbohydrates are dramatically reduced. Indeed, this challenges the argument that many weeks are required to become “fat adapted”. Furthermore, it dispels any notion that fat loss was reduced due to partial fat adaptation. At least from a metabolic perspective, maximal fat oxidation and adaptation occurs quite rapidly. At this stage, I have seen no evidence either to support the idea that if a longer period of time (on a VLC diet) was provided, fat oxidation efficiency would have been further augmented with increased body fat loss.

Based on the data at hand one could argue the opposite to that proposed by the carbohydrate-insulin model of obesity, with very low insulin levels actually blunting the rate of fat loss. Certainly in the short term at least, the rate of proteolysis was up-regulated as demonstrated by the increase in nitrogen excretion following transition to the VLC diet. Consequently, energy metabolism of participants on the VLC diet required an increased reliance and utilisation of protein from lean body mass to meet energy needs. Over the long-term, negative nitrogen balance and increased catabolism of lean body mass is undesirable but fortunately this change only subsisted until day 11. In spite of this, the blunted rate of fat loss persisted from this point to the end of the study as demonstrated by the DXA results. The nitrogen excretion, RQ, 24-hr C-peptide and DXA data support that the rate of fat loss observed was as good as things were going to get.

Notwithstanding the recent publication and thought provoking work of Professor James Johnson and co (using rodent models and experiments) that proposes a direct causal role for hyperinsulinemia in obesity, results of human studies are less convincing and not conclusive. The current study under review is a case in point, given that the dietary modulation and significant/persistent reduction of insulin did not translate into greater fat loss as would be anticipated if causality was prominent. This is a particularly incongruous outcome that contradicts and questions the fundamental underpinning of the carbohydrate-insulin model of obesity, given that insulin levels did not apparently affect, or were correlated to, the rate of fat loss.

Adipose cell size changes and regional fat deposition as predictors of metabolic response to overfeeding in insulin-resistant and insulin-sensitive overweight/obese human subjects in the McLaughlin et al. (2016) study, also reported results which were opposite to that expected by the researchers. Interestingly, insulin-resistant subjects showed, as would be expected, significantly greater hyperinsulinemia at baseline and at peak weight following the intervention, but surprisingly tolerated and responded better to overfeeding than did insulin-sensitive subjects. The authors state:

In contrast to our hypothesis that IS subjects would demonstrate adaptive adipose tissue and metabolic responses to weight gain, we found the opposite: IS subjects exhibited maladaptive adipose tissue responses and developed clinically significant insulin resistance. Adipose mass expanded in the visceral and intrahepatic depots, and adipose cell hypertrophy was evident. FFA concentrations under steady-state insulin conditions increased by 133%, indicating resistance to insulin suppression of lipolysis, whereas AUC FFA concentrations after a standardized test meal were not increased, likely due to concomitant increases in the insulin AUC. Muscle insulin resistance, as measured by SSPG, worsened by 45% in the IS group compared with 8% in the IR group with similar weight gain. Interestingly, the magnitude of change in all of these variables, including VAT, IHL, adipose cell peak diameter, and insulin suppression of lipolysis, significantly predicted the degree to which SSPG worsened. Further, these associations were independent of weight gain per se, implying that differential cellular and regional fat distribution patterns of adipose tissue may contribute to the metabolic heterogeneity of obesity.

The results of the abovementioned studies and other human trials show, as stated by Hall and co in their study, that “it is clear that regulation of adipose tissue fat storage is multifaceted and that insulin does not always play a predominant role.” Results like these raise another very pertinent question. Just how relevant are experiments in rodents and their related models of disease, when the results of human research is discordant to their postulations?

Now to the crux of the matter.

The body composition results of the Hall study confirm and add to over 80 years of scientific research that conclusively demonstrates that when it comes to weight or fat loss, the laws of energy balance hold true. Since the early 20th century at least 30 tightly controlled metabolic ward studies have been conducted and they resoundingly find the same thing. Regardless of one’s age, race or gender, for an increase or decrease in body fat to occur, a commensurate positive or negative energy imbalance, respectively, must exist. Whilst there may be some advantage of higher protein diets preserving or increasing LBM (see here, here and here for example) and insulin resistance status possibly influencing response to different diets (see here and here for example), fat loss achieved by manipulating the proportion of energy derived from carbohydrates and fat in isocaloric diets, is not significantly different.

An assessment of the research where study participants are confined to an in-patient metabolic unit/ward/chamber are the most accurate way to scientifically determine the specific energy requirements needed for weight change. Such studies are expensive because they are very resource and equipment intensive. However, what they allow researchers to do is measure what is being consumed (energy in) and what is being expended (energy out) quite precisely – or at least, a lot more precisely than studies that involve free-living subjects.

The methodology of such studies looks something like this. For the duration of these trials subjects’ have to remain in the hospital or unit and in some cases, spend time in metabolic chambers. Participants are allocated and given all consumables (food and drink) for the duration of the intervention. The caloric content of what is consumed is a known entity and has been prepared and accurately measured. The macronutrient percentages of the diet for protein, carbohydrates and fat has been determined. Physical activity is closely monitored, measured and accounted for. Resting EE and total daily EE is measured as accurately as possible based on the equipment available and methods employed in the study.

With energy intake (EI) and energy expenditure (EE) measured as close to actual as possible, investigators can now establish whether firstly, the prerequisite for weight or fat loss is an energy deficit, and secondly, if macronutrient composition exerts differential effects on such loss. Evaluation of such research has shown that no major differences have been found for weight or fat loss when macronutrient diverse isoenergetic diets are compared. Results from these studies show beyond dispute that the fundamental determinant for decreased weight is a caloric or energy deficit, not diet composition. To look at the evidence another way, not one of these trials – not even one – has ever been able to demonstrate a decrease in weight (excluding loss of water weight) or body fat when daily EE is less than daily EI. This remains so irrespective of the macronutrient breakdown. If a “metabolic advantage” of VLC diets truly existed, researchers should be able to show under tightly-controlled metabolic unit/chamber conditions, decreases in fat mass when changing from a isocaloric HC weight maintenance diet to a isocaloric-matched VLC diet (Hall’s study attempted to do this but the unintentional weight and fat loss slightly altered the course of the study). Obviously, such a dietary change will yield decreases in weight due to changes in water balance as described above (see Kreitzman et al (1992) & Yang and Van Itallie (1976)), but there has never been any methodologically sound and robust published research (under ward conditions) to show that greater fat loss is facilitated by isoenergetically swapping out carbohydrate for dietary fat.

Below is a small selection of these metabolic ward-based studies and their key findings to illustrate the aforementioned.

Keeton & Bone (1935) – No difference in weight loss diets low in calories containing varying amounts of protein.

Werner et al. (1955) – No difference in weight loss for the low-carbohydrate, high fat diet versus high-carbohydrate diet.

Yang and Van Itallie (1976) – No difference in fat loss for an 800 kcal/day ketogenic versus non-ketogenic diet. The authors state: “Rate of fat loss was a function of degree of energy deficit.”

Leibel et al. (1992) – No difference in body weight or stability during very wide variations in the fat-to-carbohydrate ratio (fat energy varied from 0% to 70% of total intake) with no significant variation in energy need. Sixteen human subjects were confined to a metabolic ward for an average of 33 days and fed precisely known liquid diets with protein derived from milk, carbohydrate as cerelose and fat from corn oil.

Golay et al. (1996) – No difference after 6 weeks for weight loss, fat loss or waist-to-hip circumference. This study compared diets equally low in energy (1000 kcal) but widely different in relative amounts of fat and carbohydrates on body weight reduction in 43 obese adults during a 6-week period of hospitalisation. The diets were composed of 32% protein, 15% carbohydrate and 53% fat versus 29% protein, 45% carbohydrate and 26% fat.

Stimson et al. (2007) – No difference in fat loss for the isocaloric phase of the study period.

Graves et al. (2013) – No difference in BMI or weight reduction for the 3-week inpatient period for each diet (or for the 48-week outpatient treatment).

Hall et al. (2016) – No difference for body fat loss for the VLC versus HC diet.

There are many other such studies but the overall findings tell the same story, which is that the fundamental arbiter of weight or fat loss is the existence of an energy imbalance where total daily EE exceeds EI. One of the largest meta-analyses and systematic reviews available, the massive 2014 review by Naude and colleagues titled “Low Carbohydrate versus Isoenergetic Balanced Diets for Reducing Weight and Cardiovascular Risk: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis”, assessed as many as 228 studies including those with free-living subjects. The authors reached the same conclusion and stated:

The similar reported mean energy intakes in the low CHO and balanced diet groups and the corresponding similar average weight loss in the diet groups supports the fundamental physiologic principle of energy balance, namely that a sustained energy deficit results in weight loss regardless of macronutrient composition of the diet.

So let me put some social media context on this. The next time someone makes the claim that “calories don’t matter” or “the concept of energy balance has been debunked” or “has no scientific basis”, ask them why the most controlled, rigorous and accurate methods used by researchers has repeatedly proven the concept to be valid and hold true over the last 80 years or so.

Before I finish up this section I need to make some clarifying comments.

There will be those that read this and conclude that what I am suggesting or all that I think matters is calories, with diet quality just a cursory concern. I can hear some of you saying right now “….but surely 2500 calories of jelly beans or junk food is different to 2500 calories of atlantic salmon, walnuts, broccoli and berries.” Really? Well, yes, of course it is, thanks for pointing that out. A diet consisting of wholesome, natural, minimally processed and nutrient-dense foods is paramount to ensuring good health. I should state now that I am not suggesting for one moment that the quality of the diet is not important. Irrespective of how good a diet is, the fact remains nonetheless that it is still possible to gain weight eating a wholesome, natural, minimally processed and nutrient-dense diet. It is probably much more difficult to do so, but regardless, you cannot escape the fact that you have to be in a consistent calorie deficit to lose fat or a chronic caloric surplus to gain fat.

With all of the above being said I remain of the firm belief that further research is warranted. Among many issues that remain outstanding and require elucidation, I am particularly interested in seeing more research on such things as:

- Does altering the macronutrient composition of the diet (fat for carbs) elicit an inequivalent effect on appetite satiety with an inadvertent spontaneous reduction in food intake? There is certainly some evidence to support this.

- Does swapping out carbohydrate for increased dietary fat provide benefit to those with metabolic abnormalities such as insulin resistance and type-II diabetes? Once again, there is evidence to support this also.

The only thing I will say about these questions is that the published research is somewhat mixed. Three meta-analyses and systematic reviews do not concur on whether metabolic outcomes are affected by manipulating the macronutrient composition of the diet. Naude et al. (2014) and Boaz et al. (2015) concluded that there were no differences on metabolic outcomes when the protein, carbohydrate and fat composition of the diet was varied. In contrast, Schwingshackl and Hoffman (2014) suggested the opposite stating that dietary manipulation in favour of increased fat did alter metabolic outcomes. More work is obviously required but I suspect that diet quality is going to have a significant role to play based on the findings of Veum et al. (2016) where consuming energy primarily as carbohydrate or fat for 3 months did not differentially influence visceral fat and metabolic syndrome in a low-processed, lower-glycemic dietary context.

Finally, I would like to suggest that what we cannot and should not invest anymore time or money researching or debating, is whether or not the energy balance model holds true. Based on our best science suggesting otherwise is moot. The jury is in. We can debate, argue and disagree about the ‘why’ in relation to the growing rates of obesity but not the ‘how’. In the words of Stephan Guyenet, “….the evidence suggests a simpler and more compelling explanation: We eat too much food that is obviously unhealthy, and it’s not because researchers or the government told us to, but because we like it.”

Spontaneous Physical Activity

The inclusion of the low intensity cycling was an interesting component of the Hall study which was prescribed, as explained in correspondence to me, to prevent the usual decrease in physical activity that occurs when people spend many days as inpatients on a metabolic ward. The data supports that this was achieved. In fact the physical activity levels and energy expenditure recorded for this metabolic ward study (inside and outside the chamber) are quite impressive. The total daily EE measured during chamber stays (EEchamber) was over 2600 kcal/day for both diets. Physical activity expenditure on days outside the chamber (PAEnonchamber) and total daily EE certainly suggest that the participants were far from sedentary and in fact quite physically active. Assuming sedentary energy expenditure (EEsedentary = SEE + AFT) was consistent and similar inside and outside the chamber – and there is no reason why this wouldn’t be the case – the total daily EE when outside the chamber exceeded 3100 kcal/day and 3300 kcal/day for the HC and VLC diets, respectively.

For the HC diet for example, total daily EE when outside the chamber would approximately equate to:

- EEsedentary + PAEnonchamber

- (1.34 kcal/min x 60 x 24) + (1221 kcal/day) = 3151 kcal/day (See table 2 below).

In my mind, total daily EE and physical activity of this level in similar free-living adults is not representative of sedentary levels of activity. It would therefore surprise me if total daily physical activity EE of these participants, prior to this study, was this high. This may go some way in explaining the unintentional weight loss that occurred during this study. The combination of the daily clamped cycling exercise (∼300 kcal/day) and the increased SPA outside the chamber (>500 kcal/day) appears to have contributed to the overall state of negative energy balance and concomitant body composition changes.

Physical activity EE outside the chamber (PAEnonchamber) was found to be 126 kcal/day higher but was statistically nonsignificant at the end of the 2 month inpatient stay. This was a sum total of: 1) energy expenditure for 90 minutes cycling at a clamped intensity (EEexercise) and; 2) spontaneous physical activity (SPA) energy expenditure.

Given that the low intensity cycling was performed at a clamped intensity and based on the data that no difference existed for EEexercise for both diets during chamber stays (see table below), it is reasonable to assume that EEexercise when outside the chamber would be similar for both diets too. The 126 kcal/d difference between the HC and VLC diets in PAEnonchamber can only be accounted for, then, by increased SPA. The authors of this study allude to this in their discussion (pg. 332) saying: “Despite slight positive energy balance during the chamber days, the overall negative energy balance amounted to ∼300 kcal/day and was likely due to greater spontaneous physical activity on nonchamber days.” However, the exact increases in SPA outside the chamber were not directly reported in this paper. Obviously, it is important to recognize and indeed be reminded before exploring the possibilities that could explain this increased nonchamber SPA, that there was no statistical significant difference shown for PAEnonchamber. As such, the discussion below is largely speculative and purely an exercise in intellectual curiosity.

Notwithstanding, the difference may be related to:

- The time spent on the metabolic ward caused behavioural-induced SPA alterations.

- The VLC diet had a direct modulating effect on SPA.

- Increased SPA was influenced by increased fitness and/or fat loss over the course of the study.

Time spent on the metabolic ward led to behavioural-induced SPA alterations

The first explanation posits “that the subjects’ behaviour was affected by the time spent on the metabolic wards” with subjects anxious to finish the inpatient study. However, this explanation whilst appearing sound in theory is not supported by the results of the study. For this behavioural-induced increased PAEnonchamber explanation to be consistent and valid, you would expect to see by the end of the study as well, the same type of relative change in PAEchamber. That is, both SPA inside and outside the metabolic chamber would change in a comparable way, both in direction and relative magnitude. This was not the case though with SPA inside the chamber being lower, albeit minimally, in the VLC phase of the trial compared to the HC diet (0.1963 vs 0.2241 kcal/min; p=0.0102). This corresponds to ∼40 kcal difference over 24 hours – a statistically yet arguably clinically irrelevant difference. In contrast, SPA outside the chamber was non-statistically higher for the VLC vs HC diet. It is this discordance for chamber vs nonchamber SPA and diet type that makes it unlikely that behavioural change drove the increased PAEnonchamber by the end of the study.

SPA was directly impacted and increased by the VLC diet

Supporters of the “metabolic advantage” theory would interpret the higher PAEnonchamber (due to increased SPA) as suggestive that the VLC diet had a direct impact on physical activity levels. But how precisely or by what mechanism(s) decreasing dietary carbohydrates translates into increased physical activity EE is anyone’s guess. I am yet to be convinced and have found no compelling research that altering the macronutrient composition of the diet alters SPA in any significant way. Furthermore and as discussed above, SPA for both diets differed for PAEchamber versus PAEnonchamber. The question then is why would SPA increase when outside the chamber and decrease when inside the chamber when the VLC diet is compared to the HC diet? If diet truly changed this parameter of energy expenditure, a consistent effect would be expected irrespective of setting.

Increased fitness and/or fat loss led to increased SPA

Another possible explanation for the increased PAEnonchamber is that a training effect of the low-intensity cycling and accompanying weight loss affected SPA levels. As such, my proposition is that this is not directly related to the dietary intervention at all. Let me explain. Not knowing how active or inactive the participants were prior to entering this study (I’m assuming given the description that they were not doing much physical activity at all in the lead up to the study), it is plausible that the 90 minute cycling performed each day during the study was over and above what they were doing beforehand.

If that is the case, logic would suggest that it is probable that participants would have increased their cardiovascular fitness over the duration of the study despite the clamping of exercise intensity, being confined as an inpatient to a metabolic ward and spending 16 days over 2 months in a metabolic chamber. As mentioned above the low intensity cycling was included in an attempt to offset the usual decrease in physical activity that occurs during metabolic ward studies. Whilst sedentary-like behaviour can mitigate the positive effects of aerobic exercise, the data for PAEnonchamber and total daily EE suggest that such behaviour was largely curtailed. This supports the possibility that the combination of the cycling exercise and high levels of SPA facilitated increased cardiovascular fitness.

This improvement in fitness and concomitant fat loss may have, then, inadvertently affected SPA with increased expenditure during the 2nd month of the trial. There is some evidence that exercise, improved fitness and fat loss lead to increased SPA in some people. In a study by Manthou et al (2010) which explored the behavioural compensatory adjustments to exercise training in overweight women, the loss of weight/fat mass or lack thereof, was attributable to an increase or decrease in SPA, respectively. Physical function and peak oxygen consumption has also been shown to improve significantly more in older obese men randomized to an exercise-diet intervention (with accompanying weight loss) compared to a diet-only group (with accompanying weight loss) or exercise-only group (with no weight loss), with improved functionality and fitness correlated to increased levels of SPA. This explanation has one major caveat however with an underlying assumption that SPAchamber remained unaffected by improved fitness and fat loss due to a curbing effect of confinement. This is a big assumption which thereby leaves us with our last explanation and basically brings us full circle to what the results originally showed.

That no real difference existed as suggested by the statistical analysis

The final explanation is that PAEnonchamber and SPA did not differ between diets. The most compelling evidence to support this is that no meaningful difference was found between diets for fat loss or body composition. If such a difference in SPA actually existed, a difference in body composition should have been detectable.

Final remarks

The recent study conducted by Kevin Hall, Kong Chen, Juen Guo, Yan Lam, Rudolph Leibel, Laurel Mayer, Marc Reitman, Michael Rosenbaum, Steven Smith, B Timothy Walsh and Eric Ravussin demonstrated that a VLC diet was no more effective compared to a HC diet for reducing body fat. Increases were detected in EE for the VLC diet but the clinical relevancy is of dubious value given that this was a transient phenomena, significantly decreasing linearly over time with EE returning to baseline by the end of the study. The results provide further confirmation of the fundamental physiologic principle of energy balance and reinforce that a sustained energy deficit results in weight loss regardless of macronutrient composition of the diet. Despite insulin secretion and respiratory quotient being dramatically reduced during the VLC diet, no enhancement of fat loss was evident. This provides compelling evidence that the regulation and storage of fat in the adipose tissue is far more complex and nuanced in humans, with insulin not always playing a predominant role. Further investigation and research is warranted to elucidate any appetite attenuating and metabolic benefits of higher-fat diets.

Disclaimer: All contents of the FitGreyStrong website/blog are provided for information and education purposes only. Those interested in making changes to their exercise, lifestyle, dietary, supplement or medication regimens should consult a relevantly qualified and competent health care professional. Those who decide to apply or implement any of the information, advice, and/or recommendations on this website do so knowingly and at their own risk. The owner and any contributors to this site accept no responsibility or liability whatsoever for any harm caused, real or imagined, from the use or distribution of information found at FitGreyStrong. Please leave this site immediately if you, the reader, find any of these conditions not acceptable.

© FitGreyStrong